2009 Civil War Travelogue (part 2)

| Here is a reminder about the reason I write these pages the way I do. They record my experiences and impressions of Civil War trips primarily for my future use. Thus, they sometimes make assumptions about things I already know and focus on insights that I receive. They are not general-purpose descriptions for people unfamiliar with the Civil War, although I do link to various Wikipedia articles throughout. Apologies about the quality of interior photographs—I don't take fancy cameras with big flashes to these events. If you would like to be notified of new travelogues, connect to me via Facebook. |

University of Virginia Civil War Conference: Petersburg to Appomattox, May 27-31

Three years ago, I had the pleasure of attending my first in a series of recurring conferences sponsored by Gary Gallagher of the University of Virginia. These have been going on for over 20 years, stepping their way somewhat sequentially through the various campaigns of the war (at least the Eastern ones, to my knowledge) and they have finally reached the last one in Virginia. See the conference program.

One of my practices before attending conferences of this type is to ensure that I have all of the related Wikipedia articles up to snuff, which helps me focus my preparation. This time, I made a real tactical error. Assuming that this conference would start off where the previous one ended—right after the Battle of the Crater—I started doing intensive work on the basic Siege of Petersburg article and found that it was an enormous amount of work because most of the individual battle articles that are collected in the campaign article needed a lot of work as well. So I got about two thirds of the way finished with that before I ran out of time. But when I got here, I suddenly realized that the itinerary started at the complete tail end of the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign, the Battle of Fort Stedman. Almost the entire focus of the conference would be on the Appomattox Campaign and I found to my disgust that that article was in really bad shape—I had not touched it since my very early days on Wikipedia. So I spent a few hours in the hotel room doing a cleanup so that it is not totally embarrassing if anyone figures out I am responsible for it. I will get to a general improvement after my return.

I flew to Richmond on Tuesday, May 26, because the program started early enough in the afternoon on Wednesday that I could not make it from California that same day.

Wednesday, May 27

I got up bright and early to visit some Richmond battlefields that I knew would not be on the conference agenda. The Richmond-Petersburg Campaign had at least six battles north of the James River, a few of them quite notable. I started by driving to Deep Bottom, which is the crossing point on the James River used for many of those battles. It is just a simple county park today with a fishing boat ramp, but I got to see a nice view of the opposite bank and imagine the pontoon bridge crossing over it. Then I drove along a series of Union and Confederate fortifications that had significant roles in the Battle of Chaffin's Farm and New Market Heights, September 29-30, 1864. This was an interesting battle that has historical significance as arguably the most important one in which African-American troops fought. Of the 16 Medals of Honor awarded to United States Colored Troops (as they were called at the time), 14 of them were issued for heroism in storming fortifications in this battle. The main fortification, Fort Harrison, is remarkably well preserved, although covered with grass. There is also a little NPS visitor center and I watched a brief but informative movie about the battle. The other fortifications were also nicely preserved, but warranted little more than a few roadside signs: Forts Brady, Hoke, Johnson, Gregg, and Gilmer, and Battery Alexander. Unfortunately, the New Market Heights part of the battle isn't well preserved and the park ranger told me there was little to see.

Deep Bottom |

Fort Harrison |

Drewry's Bluff |

Next I crossed to the western bank of the James River and visited Drewry's Bluff. This was the site of a naval battle in 1862 as part of the Peninsula Campaign—Union gunboats attempted to sail up the James River and bombard Richmond, but the big guns in Fort Darling prevented their passage. The fort is a brief walk through the woods from the highway and it is also nicely preserved, although it really has very few interpretive signs. You get a good view of the river and can imagine how commanding the artillery was. (Drewry's Bluff also figured in the 1864 Bermuda Hundred Campaign, but except for a single paragraph on the wayside sign, there is no mention of it.) Driving into Richmond, I stopped at the Richmond National Battlefield visitor center, which is located in the old Tredegar Iron Works. They also had a brief movie, which was nicely done, focused primarily on the 1862 campaign around Richmond. They had a pontoon bridge boat on display, accompanied by a scale model of a fully deployed pontoon bridge, which I thought was pretty interesting. I can't say that I found the iron works itself all that fascinating.

Lincoln Statue at Tredegar |

Tredegar Iron Works |

At the University of Richmond, which is a beautiful campus (although maddeningly difficult to find when you're driving there, even with a GPS), I registered for the conference. Most of the attendees are staying in the dormitory, but I got sick of that regime when I attended a few Gettysburg College seminars, so I am commuting from a hotel 10 minutes away. In the lecture hall that afternoon, we were welcomed by the university president, Edward Ayres, a Civil War author himself, and started off with two one-hour long lectures.

Edward Ayres |

Gary Gallagher |

Gary Gallagher gave an overview of the Appomattox Campaign. As usual, Gary is an interesting and engaging speaker, although in this case he deliberately kept to a narrative overview, so for anyone who had done their homework, there was little new information or insight. He was followed by Bobby Krick (Robert E. L. Krick, whom Gary calls "Relk"), assigned the topic of the High Command of the Army of Northern Virginia. We found out while he was being introduced that he is working on a book about the Battle of Gaines' Mill, which I am looking forward to. Bobby's talk was primarily a series of interesting anecdotes about the generals and I made notes about a number of tidbits:

- Lee's primary headquarters during most of the Richmond-Petersburg Campaign was not in Petersburg, but north of the James at Chaffin's Bluff.

- Lee frequently deployed what Bobby called "battle groups" that mixed up the various available divisions where they were needed, rather than relying on a strictly hierarchical corps structure.

- Bobby identified what he called "emerging heroes": William Mahone, John B. Gordon, Charles W. Field (about whom not a lot is known because he was seriously wounded at Second Manassas and was out of the war for two years before returning to command most of the troops north of the James, before Longstreet returned), and surprisingly, A.P. Hill, whom Lee called upon whenever immediate, urgent assistance was needed.

- Bobby particularly admires Bryan Grimes, a general I'm not too familiar with, because of his frankness and belligerent stance.

- Considering the 62 Confederate generals and very senior officers at First Manassas, only one of them made it to April 9, 1865: Longstreet.

- At the end of the Appomattox Campaign, Joseph B. Kershaw's division had zero generals and field officers (majors and up) left.

Bobby concluded with a discussion of the three generals who were dismissed by Lee very late in the campaign: Richard H. Anderson, Bushrod R. Johnson, and George Pickett. The latter is the most controversial, and after weighing the available evidence, Bobby does not think that is possible to tell whether he was actually relieved or not, and if so, whether he was ever notified. (I discuss some of these issues in my Wikipedia article, George Pickett.)

Bobby Krick |

Bill Bergen |

We broke for dinner in the new college cafeteria, which is exactly like a modern corporate cafeteria, reminiscent of a shopping mall food court, but the difference here is that there is one admission price (in our case, included with the conference fee) and after that is all you can eat. This is going to be real trouble. After dinner, we went back to the lecture hall where Bill Bergen talked about the Union high command. He discussed some of Grant's leadership traits, his strategy for the simultaneous advances in all theaters in 1864, and went through capsule descriptions of all of the major army and corps commanders. He also spent some time talking about how Philip Sheridan relieved Gouverneur K. Warren after the Battle of Five Forks. Those folks staying on campus then adjourned to another building for a special dessert reception, but I chose to head back to the hotel, avoid the calories, and spend some time on this report.

Thursday

Keith Bohannon started us off with an hour on John B. Gordon and Fort Stedman. It is amusing when historians track different versions of veterans' stories. In Gordon's case, his estimates of enemy strength and Confederate difficulties increased substantially from his recollections in the 1870s to his memoirs in the late 90s, as did his personal role in advising Lee on strategy near the end of the war. A couple of points I found interesting: Gordon's otherwise elaborate plan was vague about what would happen once his three 100-man advance elements reached the Union rear area. He spoke about capturing a secondary line of forts, but there is considerable disagreement about what forts he was referring to—perhaps the old Dimmock Line fortifications—and apparently his men had the same problem. Also, he had six brigades in reserve that he didn't use.

Keith Bohannon |

Peter Carmichael |

Bob Krick |

Peter Carmichael spoke for an hour on Five Forks and I really enjoyed his approach. He framed the discussion around historical sketches and paintings, pointing out some of their gross errors, but also their historically truthful themes. (Sheridan is usually shown leading gallant cavalry charges, but the battle was decided by the infantry. However, Sheridan did have a personal role in driving the course of the men and battle. Peter said he "electrified" it.) He told us about a quote from Clausewitz, something to the effect of "If you can see it, you can't know it," referring to the inability of individuals to understand the big picture of a battle they've been in. I noted in my nerdy way that that's essentially Heisenberg's Uncertainty Principle. I was pleased to see that Peter used one of my Petersburg maps for his talk and he mentioned me to the audience. He compared Lee and George Pickett to Andy Griffith and Barney Fife—reluctantly trusting him, but only with one bullet. He commented on the famous quote attributed to Lee about holding Five Forks "at all hazards," which he implied was manufactured afterward by Sallie Pickett, saying that this unnecessarily tied Pickett's hands, because the position was indefensible. He also called Gouverneur K. Warren the James Longstreet of the Army of the Potomac, always challenging orders and slow to implement them, giving some insight into Sheridan's somewhat-justifiable relief of Warren.

Bob Krick, father of Relk, spoke on the defense of Fort Gregg, the "Confederate Alamo." He started by reviewing some of the famous "last stands" in U.S. and world history, such as Custer's and the real Alamo. The 300 Confederates in Fort Gregg were hit hard by 5,000 Union troops during the Petersburg breakthrough on April 2. The fort was formidable, but only built up on three sides; the northern face was covered by artillery from the adjoining fort, however. Bob referred to "vivid accounts ... that almost defy belief," although he didn't go into much detail. He spent about as much time describing the difficulties for the Union guys to scale the 20-foot mud walls as the plight of the defenders. The latter were all casualties, including about 150 surrendered, so it wasn't quite like the real Alamo at the end. Alan Nolan wrote critically of Lee that his decision to defend this point demonstrated his blood lust, which seems like a stretch. An interesting sidelight: Archibald Gracie, IV., son of a general killed here, and the most prominent of the Petersburg battlefield preservationists, was a survivor of the Titanic. There are widespread accounts of him dying with the ship, but since he wrote a book about the experience, that conclusion is unlikely.

|

|

|

Carrie Janney |

Steve Cushman |

Joan Waugh |

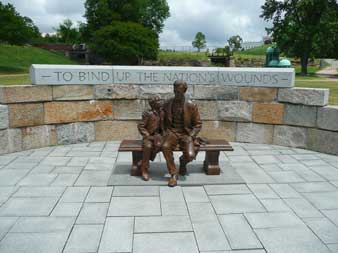

Caroline Janney spoke on "War at the Shrine of Peace: The Appomattox Peace Monument and the Retreat from Reconciliation." This was a very interesting talk about a very narrow subject, you would think, about why there is no peace memorial sculpture at Appomattox. In the 1890s, there was some desire to establish a National Military Park comparable to Chickamauga, Gettysburg, etc., but by the 1920s, the War Department rejected this idea, saying that there was no significant battle there and therefore it could not be considered a "tactical classroom." (The War Department partially justified the establishment of military parks as a way to train its officers in tactics and strategy.) There was a bill introduced in Congress for a peace monument, but it went nowhere and by the 30s, many of the good feelings of reconciliation that had been prevalent in the 1880s and 1890s had passed away. The veterans were apparently much more tolerant of each other than their descendents were. Carrie quoted a document from the Grand Army of the Republic in which it called the United Daughters of the Confederacy the "country's worst enemies." By the early 30s, the War Department issued a call for proposals and the winning design was a column that had carvings of both Lee and Grant on a common base. This caused an eruption of outrage in the South, which resented Grant primarily for his role in Reconstruction. They also objected to a memorial effectively celebrating the South's loss, and the proposal died when the Interior Department took over the site. (I remarked that it was just as controversial to have two West Pointers on the same monument.) As an alternative, money was designated to rebuild the ruined village of Appomattox Court House. Carrie showed an interesting photograph from the early 1900s in which the famous McLean house was simply a pile of rubble and apparently the courthouse was in the same state.

Stephen Cushman, who is an English professor at the University of Virginia, gave a very interesting talk about Joshua Chamberlain and Appomattox. Chamberlain has a reputation as a serial exaggerator and self promoter and this talk looked into the claims he made over the years about ordering a salute to the Confederate troops as they marched by following the surrender. (Stephen offered an interesting aside that the word Appomattox is an Indian one for "sinuous tidal estuary.") He offered a document that showed six different versions of the story that Chamberlain wrote over a 50 year period. As they progressed, passive verbs turned active and responsibilities of unnamed plural individuals turned into first-persons. (An order was given, we gave an order, I gave an order.) Part of the controversy here is some very vituperative writing from William Marvel, who has lambasted Chamberlain in two books about Appomattox. Stephen did not render an absolute judgment, but seemed to be sympathetic to Chamberlain's veracity, suggesting that adding details over time does not necessarily indicate an intent to deceive, and in fact the minor variations over the years lend some credence to the story because they did not contain the lockstep recitation of identical claims that a falsehood might have. He offered an interesting quotation from Grant, which I think is appropriate for Chamberlain's case: "Wars produce many stories of fiction, some of which are told until they are believed to be true." And he gave me a good trivia item I will have to verify: Chamberlain was the only man in the V Corps to receive a Medal of Honor.

Joan Waugh spoke about Grant and the surrender negotiations. She took us through his previous two surrenders (Fort Donelson and Vicksburg) and illustrated how terms he used there affected his ACH behavior. She called his magnaminious terms and the meeting at the McLean house a "supremely perfect moment in our national history." We concluded the day with a brief orientation about the Friday and Saturday bus tour schedule and logistics. A lot of driving coming up...

Friday

Up early for a 7:30 a.m. bus departure and our first day of touring. We started by driving to the Petersburg Battlefield to visit Fort Stedman. I had actually visited Stedman before, but now I had a lot more context on the battle. It was great to see the actual dimensions of the fort (about three quarters of an acre in size) and how it related to the neighboring artillery batteries as well as the Confederate line at Colquitt's Salient. Unfortunately, the National Park Service discovered some eagles nesting and we were not allowed to cross the no man's land to see the Confederate position. Bob Krick said that he was pretty sure the eagles had departed a couple of years ago, but the NPS people were reluctant to remove the restriction, wanting to keep their "green" credentials well-polished. This is actually a satisfying battle to visit because it is extremely straightforward—the Confederates sneak in, capture the fort, drive a little ways into the Union rear area, but are then repulsed.

Fort Stedman |

Recreated fortification at Pamplin |

Earthworks at PB Breakout |

We left Petersburg and drove out on the Boydton Plank Road to see the battleground of the Battle of White Oak Road, which was part of the maneuvering to turn the Confederate right flank before the fall of Petersburg. It was an important battle because the Confederates lost control of the Boydton Plank Road and the South Side Railroad, and George Pickett's Division was isolated from the rest of the Confederate line. The Civil War Preservation Trust has somewhat recently preserved 880 acres, which covers the principal battlefield. We walked along a woodsy trail and visited an artillery placement, although there is not really a lot else to see here. The best part of this stop was a lengthy heated argument between Gary Gallagher and Bob Krick about whether Grant or Lee was the bloodier general. Gary has long espoused the opinion, which I agree with, that Lee was the most aggressive general of the war and that his soldiers suffered more casualties proportionately than Grant's. (According to Gary, if you joined the Army of Northern Virginia, you had an 80% chance of being a casualty during the war.) Gary not only disagreed with Bob, but he was indignant that Bob seem to believe what he believed. An amusing interlude ...

We drove 4 miles down the White Oak Road to the famous intersection, Five Forks. The CWPT has also been doing excellent work on this battlefield and we were told that in the 1980s, there was nothing that we could have visited on public land other than the road intersection. We walked into the woods to see the remnants of the Confederate "return" (where the Confederate earthworks took a right angle to refuse their left flank). This was where Sheridan jumped his horse Rienzi (although he was calling him Winchester by this time, I think) over the Confederate earthworks and into a group of prisoners, the incident that has been inflated in popular artwork to make it seem as if he were charging into an active defense. We drove to the crossroads and had a lunch of fried chicken. I thought this was a big loss of opportunity because they should have served baked shad, or at least Filet-o-Fish masquerading as shad. (George Pickett was notoriously away from the battlefield at a shad bake as his men were losing the battle.) At this location, Peter Carmichael gave us a biography of Willie Pegram, the gallant young artillerist who was killed during the battle.

We drove to be Gilliam house (pronounced Gillum), where Rooney Lee had warm feelings for a local girl, and near where the final assault of the battle took place. (Bob said that Rooney was described as "too big for a man, too small for a horse.") This started a big adventure. One of the three buses attempted to turn around on a dirt road and got stuck. After frantic attempts to free it by pushing logs underneath the rear tires, they eventually had to give up and call a tow truck. In the meantime, only one of the buses was available, so the itinerary had to be changed. By using cars and vans and the one available bus, we were shuttled in groups to Pamplin Historical Park, rather than our scheduled next stop, the site where A.P. Hill was killed on April 2. This was not a bad change because the park is rather interesting. We went through a museum dedicated to the common Civil War soldier and it had excellent artifacts as well as a very professional audio tour that covered any aspect of soldierly life that you could imagine. Once everyone had arrived, we took a hike to the rear area and saw the Petersburg Breakthrough site, where the Union VI Corps broke through the fortifications on April 2, fanning out to make the Confederate hold on Petersburg untenable. The fortifications were undoubtedly the most well preserved I have ever seen. They were untouched for 140 years on private property, but it is still remarkable that they are standing up after all of that rain. I'm sure that the fortifications facing the Union soldiers in 1865 are taller than what is there now, but they are still impressive.

Because of the delays with the buses, we were unable to visit our last scheduled stop, Fort Gregg, the "Alamo of the Confederacy." Fortunately, on the ride down, we caught a glimpse of it from the highway. So although it would have been nice to walk the hallowed ground, most of these forts actually look pretty similar. And no one complained because with the heat of day, we were all pretty exhausted. After everyone got back and had dinner, there was a one hour session on Civil War Book Reviews, but I decided to crash in my hotel instead. The departure time tomorrow is really early...

Saturday

Up even earlier today for a 7 a.m. departure. A lot of mileage is required for the Appomattox Campaign—Appomattox Court House is about 100 miles from Richmond. We drove down past Petersburg and briefly saw the site of Sutherland Station, a rear guard cavalry action, but one that claimed 1,000 casualties. Next was Namozine Church, a tiny 1847 Presbyterian church that seated only 75 people. It is currently owned by the Amelia Historical Society and a lady named Pearl was there to let us in and greet us. We knew we were in the South when she referred to the War Between the States and never spoke of the North or the Yankees, but simply "those people." The church was used as a hospital, including for the troops who had been rousted from Five Forks. The battle was another cavalry action in which the Union drove back the Confederates, but the Confederates bought time for the retreat of the army.

Pearl at Namozine Church |

Tablet at the Lockett House |

Confederate Cemetery |

We drove through the town of Amelia Court House, which is where Lee was expecting to receive rations, but administrative errors caused there to be only ammunition and other supplies. Outside the courthouse there was a tiny mortar that Bob Krick said had been used in the Battle of the Crater to "slaughter Yankees" and he thought it was a good thing that it was saved. I remarked, "Sure, there are a lot more Yankees left." We saw the Richmond and Danville Railroad, which Jefferson Davis and his cabinet had used only on their way to Danville 24 hours earlier.

One of Our Very Special Historians at Sayler's Creek |

We took a long drive to Sayler's Creek (also known as Sailors, but I cling to the older spelling) and had a great look at the very well preserved battlefield. (Thanks again, CWPT.) We started at the Hillsman house, which was a hospital and also in the vicinity of the start of the Union attack by Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright's VI Corps. The corps artillery was also sited there. We took a 0.8 mile hike down the hill to the creek—pretty insignificant in dry weather—and then up again to the Confederate position, commanded by Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell. Ewell was captured during the battle, although we cannot say for certain exactly where that happened. (Amusingly, there is a stone tablet on the battlefield that said Ewell "almost won" a great victory here.) There were also eight other Confederate generals who surrendered, quite a disaster for the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee was quoted as saying, "My God, has the Army been dissolved?" We doubled back to Holt's Corner, where the Confederate retreat column had split into two, and then to the Lockett House, scene of the other half of the terrible Confederate defeat. The Confederate wagon train was hung up crossing two tiny bridges when Maj. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys plowed into the infantry following it, under Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon. The interesting riff by the historians in the audience was that this was the scene of widespread destruction of Confederate war records. Bob Krick read an account of an officer throwing numerous books of records into the muddy creek to use as a sort of a corduroy road. Not a dry eye in the house.

View of the Union Approach |

Site of the Gordon-Chamberlain Salute |

Parole Printing Press |

Due to time constraints for the day, we were unable to stop at High Bridge, a place I would have been interested to see and will perhaps be able to visit someday on my own. Instead, we focused on spending time at Appomattox Court House. We had lunch there in the Confederate Cemetery, which is oddly tiny with only 19 graves, including one token Union unknown soldier. Carrie Janney gave a talk about this and other cemeteries. We spent some time examining the battle that preceded the surrender. It was a really poor position for the Confederates because it was completely surrounded by low ridges, like a punch bowl. The battle consisted of 3-5,000 Confederates pushing aside the Union cavalry that was blocking its forward progress, only to find that tens of thousands of infantry from the XXIV and V Corps were coming into position to block them. We saw the panoramic view of the terrain that the Confederates saw when these Union troops came over the ridge. This location was also once the site of a tavern called, appropriately, the Last Shot Saloon. We went to the North Carolina Monument, which is entitled Last at Appomattox and which is engraved with dozens of statistics that attempted to demonstrate how North Carolina had more of a role in the war than Virginia did. Everyone pooh-poohed the claims, including the one in which it had more troops than Virginia in the war, but since North Carolina had only 60% as many white males in their populations, this is quite ludicrous. Gary Gallagher decried the "obsession" with numbers in the war, rather an odd opinion to hear an enthusiastic sports fan. We also noted another UDC plaque that had a line chiseled off of it by the Park Service. Apparently it contained some historically inaccurate claims, but that doesn't seem like the appropriate way to correct the errors.

We walked up a relatively steep hill to follow the footsteps of the Confederates who marched to the courthouse on the day of the surrender ceremony (April 12) and saw the site of the alleged Chamberlain-Gordon salute episode. Then we had 80 minutes to explore the village, which is somewhat reminiscent of Colonial Williamsburg. All of the buildings are original except for the two most famous—the courthouse and the McLean House, where the surrender negotiations occurred. There are actors portraying soldiers, pretending to still be in 1865. There was an exhibit and demonstration with a printing press used to print out the parole documents. I learned a few interesting things here. The documents were signed by Confederate officers, not Union (who simply prepared rosters of the names of the parolees). They were used not only to ensure safe passage for the returning Confederates, but provided them free transportation on rail or boat and also allowed them to claim rations from any Federal or Confederate facility along the way. The McLean House is beautifully reconstructed and the surrender parlor looks authentically re-created. The staff attempted to get a photo of Gary and Bob shaking hands in front of the house, ending the war, so to speak, but they couldn't do it.

McClean House at ACH |

McClean Parlor, Surrender Site |

Bluegrass Quartet at the Picnic |

It was a two-hour bus ride back to Richmond. Upon our return, we had a nice picnic dinner in the quadrangle and were serenaded by a bluegrass quartet. We were all thankful that the weather was so nice all day, slightly cooler and less humid than Friday, and we always seemed to be able to find ample shade when we stopped. And none of the buses got stuck! So a very successful day.

Sunday

|

Bill, Bob, Carrie, Joan, Peter, Keith, Bobby |

We started at the civilized hour of 9 a.m. with a book raffle and I was not one of the 8 lucky winners. The rest of the conference was a Q&A with the faculty, except for Steve Cushman, who had to leave.

-

I asked [first] about the relative contributions of the Armies of the James and the Potomac during the campaigns. Bill said that the AoJ was the most political of the Union armies and that it had the USCT troops who made the biggest contributions of the war. Grant had enough confidence in Ord and the AoJ to send it our ahead of Lee's retreat. Relk implied that no one's interested in the AoJ because they can't tour Bermuda Hundred. All agreed that the AoJ contribution was excellent in the last 10 days of the war, but that was about it.Q&A — Emotional Highpoint of the Conference? - Why didn't Lee just slip away in the night? Because the government would have fallen and he needed Davis's permission.

- What would have been the effect of guerrilla warfare instead of surrender? Obvious answers, although Carrie pointed out that there was considerable violence for the next 10 years, if not reaching the level of actual guerrilla campaigns.

- How did the Lee-Davis communications compare with Grant-Lincoln? Apparently not much of this survives, but there was a discussion of arming the slaves and restoring Joe Johnston. In general, Lee and Davis related well because they agreed on all the big issues.

- There was a confusing question about what historians could change about the information of the war, which the panel interpreted as relating to incorrect information that has been widely disseminated. This prompted a discussion of the incorrect UDC plaques from yesterday. Peter thought that this sort of thing made the work of historians more interesting. He thought one of the impediments to his job was the reserved Victorian-style language used by the memoirs and letters; he wished they were more frank about their opinions.

- Who were the top generals in the war on each side, other than Grant and Lee? (Not limited to the subject of this conference, apparently.) Sherman, Sheridan, Jackson (RKK), Stuart (RELK). Bob remarked that Sheridan could not successfully command a large army unless it had more cavalry in it than the entire strength of the opposing army. Someone asked about Reynolds, but all agreed he had no record as a corps commander other than being killed at Gettysburg. Hancock was too debilitated by his wound (opinion applied to this campaign). Thomas ascended to army command with a great edge over Hood, so it's unclear what he might have accomplished under more normal circumstances.

- How did the tenor of the surrender affect Reconstruction? (I asked afterward: who was the tenor—Sheridan?). Some said that reconstruction could have turned out worse than it did, crediting the good feelings at Appomattox. Others, led by Peter, think that the Union should have cracked down more, imprisoned the leaders, and ensured that the former governments didn't slip back into power. They just postponed a lot of headaches to the 1960s.

- Someone suggested a future conference on Reconstruction. Gary said there was no chance—not enough people would go. (I wouldn't, for instance.) Where would the bus tours go? Another person wanted a conference on world history in the 1860s. Gary said this reflects an emerging academic trend toward world affairs and said it was "nitwitty." When asked if this was the last conference (the 22nd Gary and Bob have done), Gary said they would probably do another in 2011, probably in Gettysburg.

- There was a discussion of the strategy of exhaustion used in the Shenandoah Valley and Georgia. Someone recommended Grimsley's The Hard Hand of War. Eric Foner's book on Reconstruction was also recommended.

- Now that Obama's president, are blacks more interested in the war? Short answer, no. Some are interested in Reconstruction, but most focus their attention on the civil rights movement.

So, of all the questions, one person (me) asked about the campaigns that were the subject of the conference. Makes me wonder why a lot of the people bothered to attend. But that's a nit. It was a great conference, both in content and logistics, and I had a great time.

On the way to the airport, I drove down Monument Avenue and stopped to see and photograph the statues of Jackson, Davis, Lee (the best), and Stuart. Overall, I don't think Richmond is a very attractive city, but there are certainly some beautiful residential areas hidden in there.

Stonewall Jackson |

Robert E. Lee |

Jeb Stuart |

Civil War Days at Duncans Mills, CA

Here is a brief interlude as I get ready for my trip to the Shenandoah Valley. I drove up to Duncans Mills, CA, which is a tiny town near the Pacific Ocean in the Russian River Valley. They had a two day reenactor encampment, Civil War Days, which is supposedly the second-largest on the West Coast (after Fresno, presumably). I went up Sunday morning and had a fun time, although I'm not sure it was worth the five hour round trip. I attended one battle reenactment, which was nicely done, with quite a lot of artillery. It was certainly a mongrelized set of artillery pieces, a reflection on the difficulty of maintaining a full-size mainstream cannon. There were a few mountain howitzers and a couple of 3-inch ordnance rifles, but no Napoleons that I could see. There was one Parrott rifle, but it looked slightly smaller than I am used to. There were also some really miniature cannons that I did not recognize. (Also some Coehorn mortars, although they were not in operation.)

Confederate Artillery |

Union attack at the fence |

The "Irish Brigade" |

The reenactment was nicely done, although there was no narration or any indication of whether it was supposed to be a portion of a historic battle. I did see a II Corps battle flag and also one from the Irish Brigade, so it was obviously in the Eastern Theater. I roamed through the reenactor encampments and found evidence of the 1st Virginia and 7th Virginia (as well as the unlikely presence of the Confederate States Marine Corps and a detachment from the Confederate States Navy). The Union side displayed little more than the Irish Brigade. I did not get to talk to a lot of the soldiers because they were all in the mess hall at the time. I found it interesting that both sides had very elaborate presentations on medical procedures and all of the civilian visitors were crowded around those tents hearing the stories of gruesome amputations.

I also got to spend some time interacting with the artillery horses. There is a group called the California Historical Artillery Society that rescues retired trotting horses from Cal Expo (the state fairgrounds in Sacramento, where there is also a trotting track the rest of the year) and I got to hear all about how they were selected and trained. Pretty interesting. They actually have more horses than reenactors, so a number of them stayed home in Salinas. An interesting factoid is that an artillery battery had over 150 horses on the Union side. That's a lot of hay.

Artillery Team |

Confederate Encampment |

Political Fight in the Union Camp |

There was also the obligatory sutlers encampment, which I always check out, but although I am always tempted to buy some piece of recreated uniform or a sword or something, my better senses always take hold. :-) I overheard an amusing interchange between a young boy and his dad: "Which side are the good guys?" "The Confederates, son. The Yankees were the invaders of our country." "Do you mean the Yankees invaded the United States?" "Yes."