Hal Jespersen’s Normandy Campaign Trip, April 2024

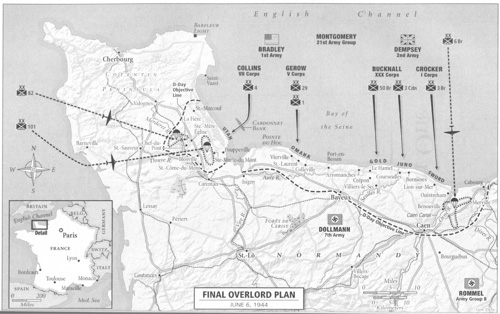

This is my (Hal’s) report of a tour of Normandy with the host of YouTube’s WW2TV, Paul Woodadge. I arranged the trip on a whim with little more than a week’s notice after hearing Paul discuss the tour on Angus Wallace’s WW2 Podcast. I had been to Normandy once before for the 75th anniversary of D-Day, a tour with Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours, described here. But I was looking for more in-depth content with more tactics and terrain, fewer crowds, monuments, and museums. And I found it—read on.

Thursday–Saturday, March 28–30 — to Paris and Bayeux

I took United Airlines, expecting to fly direct from SFO to CDG, but fate intervened. Because of unstated maintenance problems we had to deplane before taxiing and wait for new equipment, causing a three-hour delay. We took off in a replacement 777 and, while I was sleeping, we reached the Canadian border, but turned back to land at Denver around 11 pm. This incident was significant enough to make it into our San Francisco newspapers. Here I was given a hotel room, three meal vouchers and a new itinerary: fly to Miami the next morning, wait a few hours, and then take American Airlines overnight to Paris. (After I returned home I found that United comped me 32,500 frequent flyer miles for my rerouting inconvenience.)

While I understand that safety is always top priority, this was an annoying hit to my itinerary. My original plan was to stay in Paris overnight and take an early morning train to Normandy, and I had airport transfers and an interesting Paris foodie tour booked for the afternoon. My hotel was nonrefundable with this late notice, and I was left with future-use vouchers for the airport ride and the foodie tour. My train ticket to Normandy was partially refunded, but there were no trains to meet my new schedule (apparently there is a lot of line maintenance going on this weekend), so I had to rent a car at CDG, at over $100/day plus parking, gas, and tolls. This also changed my return plans. I was booked on a bus to Paris (voucher refund), where I planned to stay two nights (hotel was cancelable), with another airport transfer (partial voucher refund). So I changed my hotel to one at the airport, where the car is to be returned, and will use the RER to get into Paris for my last day. We’ll see how this all works out.

The other big hassle is that the handoff between United and American lost track of my bag. I had at least three airline people look me up in their systems and assure me that all would be fine, but then I watched us take off from Miami while my bag’s AirTag showed it sitting on the other side of the airport. After a quite decent flight on American, I registered my missing bag report and they told me I would receive my bag at the hotel no earlier than Wednesday.

I drove my rental car—the first time I have driven in Europe in about 30 years—about three hours from CDG to Bayeux, where I checked into the Hotel Belle Normandy, which is a beautifully restored old school in a couple of buildings around a schoolyard, opened less than a year ago. I walked around the nearby center of Bayeux and found it delightfully picturesque. It seems that the destruction of the Allied invasion and German resistance had a limited effect on Bayeux, unlike its neighbor to the east, Caen. I also visited the E.Leclerc “hyper-market,” like a French Walmart, where I bought replacements for some missing baggage items. At 6 pm our group met in the hotel. There are six of us, plus Paul Woodadge and partner Magali Desquesne. Over drinks, we introduced ourselves and talked about the agenda for the week. Paul handed out hardback books with photographs and color maps for each day of the agenda, which is a really classy touch. We were hosted at a dinner in a small restaurant downtown called Le Marsala, which was quite good, but really crowded and noisy the night before Easter. On the way back to the hotel, we stopped briefly to hear beautiful music at a candlelight Easter service in the huge cathedral.

Sunday, March 31 — Omaha Beach

After a delicious breakfast in the hotel, we drove to Omaha Beach, taking the D1 draw in Vierville-sur-Mer to the Dog Green landing area. Most of the day had beautiful weather, but it was pretty blustery on the beach. We arrived at low tide, just as on the invasion day, and were able to observe the sandbars some dozens of yards from the beach, which posed an obstacle for many of the landing craft and shorter infantrymen. The beach in 1944 was covered with the small stones called shingle, but Paul told us that much of it had been relocated for highway construction. There are lots of houses and some commercial properties right up on the beach, and unlike popular understanding (such as from the film Saving Private Ryan), many of these were there in 1944.

We discussed a number of aspects of the tactical surprise achieved by the Allies and Paul opined that the success of the invasion was virtually guaranteed, given all of the enormous manpower/logistical advantages and thorough preparation. He described the first wave of 60 landing craft and how they suffered almost 85% casualties, but that the second wave was less, the third even less, etc. Although the public perception of Omaha Beach is that it was a terrible bloodbath, in fact the number killed was under 900, which was serious, but not nearly enough to derail the plan. We also talked about the use of strategic bombers and how he thought the Eighth Air Force should have left the heavy bombers out of the plan, concentrating on fighter bombers that would have been more accurate.

We spent time at the National Guard monument, essentially for the 29th Infantry Division, on top of a German bunker with a Pak 43 8.8 cm gun peeking out behind a heavy steel grid. Then we walked by the sculpture called Ever Forward, honoring an American soldier dragging along a wounded colleague

We drove to the F1 draw, the easternmost part of Omaha Beach, past the American Cemetery at Collevile-sur-Mer. We walked to the edge of the bluff and witnessed the most beautiful view of Omaha Beach near Wiederstandnest (WN) 60. We saw quite visible shallow trenches in this German defensive position, and the pathway that led up to it. Paul described the exploits of Lt. Jimmie Monteith, who was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor for leading the assault on rear of this position, taking out a couple of machine guns before he was shot. Then we walked down the draw and took a long walk on the beach, traversing some of the remaining shingle, reaching WN 61, which is an imposing structure that is partially obscured by an old mobile home. Paul observed a surprising fact, which is that geologists have found that the beach area here is composed of 2% metal. He found a piece of shrapnel on the beach that we passed around.

Back up the E3 draw, we had lunch at a bistro named La Crémaillère Brasserie in Vierville, which seems to be quite popular with tourists, and is decorated with a lot of unit patches and old photographs. We returned to the D1 draw and observed structures that represented components of the Mulberry A floating harbor, the American one that was mostly destroyed in the storms starting on June 19. Instead of returning to the beach we marched up the hill and observed that the tide had completely come in right up to the seawall, in just the couple of hours we had been traipsing around. We visited WN 71 and an ammunition bunker. Here we had a discussion of the fragility of the thin German defensive line, and the relative inflexibility of their soldiers. As well, we discussed the large number of non-German soldiers manning the line and how difficult it was for them to deal with the many varieties of captured armaments with incompatible ammunition.

Paul recounted the experiences of the 5th Ranger Battalion and how its colonel, Max Schneider, encountered Brig. Gen. Norman Cota, XO of the 29th ID, who inspired the rangers’ eventual motto by shouting “Rangers, lead the f—king way.” The we went to the Dog White beach to see Cota’s Draw, but from above on the bluff, not from the beach road as most tours do. Gen. Cota, the character memorably portrayed by Robert Mitchum in the film The Longest Day, gathered up random soldiers disoriented on the beach and led them up a winding path to make the first significant inland breakthrough. Up here Paul opined that the turning point of the day was probably about 11 am, when the momentum on Omaha shifted and the beachhead was becoming solid (earlier than some accounts).

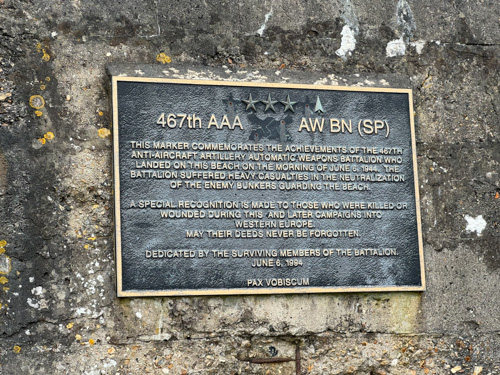

Next was E1 draw and the Easy Red beach, where we visited WN 65. We saw the winding path over which Lt. John Spalding of E Co, 16th Infantry, led his men to crawl up to the top of the bluff, unaware that he was traversing a mine field, and attack the Germans in their rear. Lt. Harlan Reynolds also attacked, bypassing the minefield by crossing a pond. Both officers received the Distinguished Service Cross. We also examined a large bunker with a 50mm antitank gun that was put out of action by troops firing anti-aircraft guns. This building was later used as an engineer headquarters and there is a plaque commemorating various engineer and admin groups, including a company of the 602nd Camouflage Engineer Battalion. I found this interesting because my father was with the 604th. He arrived in Normandy a week or two after D-Day.

We went down to the beach road for a view of Cota’s Draw from below, which I did not find nearly as interesting as the view from the top. About this time a big thunderstorm came through, which put a slight damper on the proceedings. For our final stop we headed toward the port city of Port-au-Bessin. Along the way we marched inland to find a memorial to the British Marine commandos, who had the mission of landing in between the named landing beaches and linking them together. There is a bunker on a hillside that we entered from which you can see an excellent view of the port. It was interesting to experience a strong smell of marijuana smoke. (There is also a stone strong point immediately looking over the harbor, but it is a Bourbon fort, not German.) The port city itself, which is known for scallop harvesting, was attacked by the commandos in door-to-door fighting and was the terminus for PLUTO, the undersea petroleum pipeline. It is a small port and a very picturesque town (which I had never heard of), and it was featured in the movie The Longest Day substituting for the town of Ouistreham, part of Sword Beach. We walked to a cafe that was repainted with the Ouistreham name, but the paint is fading and the actual Bessin name can be seen underneath.

We ended the day at a small Bayeux pizzeria called Fred’ Au, which had excellent pizza and modest wines at extremely reasonable prices.

Monday, April 1 — Commandos and British Airborne

Today was very interesting, because with a single exception, I had not previously been to the places we visited and in most cases had never heard of them or what occurred there. Just the kind of itinerary I had hoped to experience on this tour. Although everyone knows that the British and Canadians had three landing beaches, Gold, Juno, and Sword, there was actually a fourth beach in early plans. Band Beach was to be to the east of the Orne River and Canal, but the plan was not implemented. Instead, British airborne and commando troops were deployed.

We started at Merville–Franceville Plage, where we visited STP-05 (Stützpunkt, or strong point), a very substantial concrete bunker. Paul described the British plans and we observed that this area was high ground that could dominate Ouistreham to the west. We also saw that the current shoreline is completely different because this bunker and others in a line were originally right on the shore, but are now substantially back inland facing dry ground. This first bunker that we saw was completely covered with colorful graffiti, and we noted that the bomb damage from 36 Lancaster raids was minimal. We also visited the communications bunker occupied by Col. Steiner, the local commander, and critiqued the Germans’ use of communication wire buried only about a meter deep, which was vulnerable to bombing and very difficult to repair, so they were faced with a communications crisis and could not coordinate their actions. We also saw another Bourbon fort, although this one was topped by German construction. We did not visit the nearby Merville Battery. Paul took some time here to educate us on British slang, and we now know that “dog’s bollocks” is the highest compliment you can pay to something. (Paul is a very humorous guy and he has mastered an excellent series of regional British and French accents to deploy in his humor.)

The British plan was to land airborne forces in a variety of drop zones and glider landing zones in the area bordered by the Orne River and the Dive Rriver, which the Germans had blocked up and created a significant flooding obstacle. Commando troops would also approach by land from Sword Beach. Glider troops would seize the bridges across the Orne and Canal so that the airborne troops and commandos could be supplied and reinforced from Sword.

Our next stop was south at the town of Sellenelles, which was liberated by a mechanized cavalry brigade under Jean-Baptiste Piron, composed of mostly Belgian and Luxembourg troops. There was a small monument to their efforts. Then south again to the town of Amfreville, which is very picturesque and has quite a number of monuments and interpretive signs. The British force named Commando No. 4, led by Lord Lovat (a.k.a. Simon Fraser), whom Paul described as being an inbred chinless wonder, and was played by Peter Lawford in The Longest Day, fought intensive urban warfare here for 2 1/2 days, and then sat before unmoving lines for the next two months. They were in the pivot position after the US breakout in August and then the entire line began to advance to the east. We walked through a park that contains the ruins of the Amfreville Château, scene of fierce urban fighting.

In Ranville, we had a panoramic view of Ouistreham and Sword. We visited the British war cemetery there, outside a church, which has the distinction of actual burials before dawn on June 6. Another distinction is that instead of one large cross, as all similar cemeteries have, there is an additional concrete one built by British engineers while the area was occupied. There are currently about 2300 British graves, and over 300 German, the latter tombstones which are differentiated in shape by a slightly pointed top rather than a rounded top (just like Confederate graves in a Union cemetery).

We had a nice casual lunch next to Pegasus Bridge in a bistro called Les Trois Planeurs (three gliders). Then we walked to the Orne, the site of the famous bridge, although it has been replaced by a similar modern version. (The original bridge was relocated next to the Pegasus Museum, which I visited in 2019, but we did not do so today.) Paul described the glider assault in detail, marveling at how the first glider got within 47 yards of the bridge, and the following two came in right behind. He described the exploits of Lt. Dan Brotheridge, who was killed by German machine gun fire and was the first combat casualty of Operation Overlord. Paul suspects that this was actually a friendly fire incident, but no published sources are willing to admit it. The 21st Panzer Division was only 30 minutes away and Paul described how an initial Marder tank destroyer approached the bridge, but was stopped by a British soldier with a light PIAT handheld antitank weapon, causing the remaining few armored vehicles to withdraw. He also told humorous stories about Bill Millen, Lord Lovat’s bagpiper, and the soldier who took over a German 50 mm cannon and threatened a German patrol boat coming up the river (and who was unable to complete a BBC interview years later without swearing).

We followed the route of the Commando No. 4 to reach the bridge following their landing near Sword Beach. We ended up in a beach town named Luc-sur-Mer, which is in a gap between Sword and Juno. Paul said a bit about the landing at Sword and complained that historians are uneven in comparing the casualties between the US and British/Canadian beaches; many of the casualties on the latter actually occurred in the cities just yards away from the beach. He explained that there was a difference between the three beaches in that Ouistreham at Sword consisted of broad modern boulevards, while the other two beach towns were older and had narrow windy streets, meaning that congestion was a problem. We took a long walk on the beach road and visited a monument to the 46th Marine Commando and another to the 23rd Destroyer Flotilla. Paul convinced us that the destroyers were the most valuable components of the naval gunfire support. We came upon a large monument being restored that depicted in bas relief the British landing. It turns out that the man restoring the sculpture inch by inch for the 80th anniversary was the original sculptor of 30 years ago and he told us that the large figure of a woman on the left is actually an image of his mother.

We drove to a church south of town called Eglise Saint-Quentin, where there is a tiny official war graves cemetery consisting of three fallen soldiers and the cremated remains of the commander of Commando No. 1 and his wife. He died in the 90s and wished to be buried next to his men. The soldiers were killed during a September 1941 raid on Luc-sur-Mer. During the German occupation, local residents risked punishment by honoring these graves on the anniversaries of their deaths.

Next we drove out on the road near the town of Plumetot and found a large boulder that was turned into a makeshift map of the area, where Paul describe the approach and withdrawal of the 21st Panzer Division’s aborted counterattack; the commander became spooked by a large formation of gliders sailing overhead and just turned around and retreated. Paul remarked that of the 2000 monuments scattered all around Normandy, he knows of only three that were devoted to commemorating or describing German actions (unlike the American Civil War where there is ample documentation on the battlefields of what both sides were doing.)

In the town of Les Buissons there is a monument to the 9th Canadian Brigade and Paul described the confusion that two brigades numbered 9th—one Canadian and one British—with very similar sounding names of their brigade commanders, were moving forward in the same vicinity, causing a lot of communications confusion. This area is commemorated as Hell‘s Corner, referring to an ambush up the road of the Canadians by the 12th SS Panzer Regiment (of the 12th SS Panzer Division, the Hitlerjugend), in which 18 combat vehicles were destroyed and the captured Canadians were massacred by the German troops. We soon drove around the Buron town square where the massacre occurred. Col. Kurt Meyer of the 12th had a notorious history of cruel war crimes and Paul told us that after the war he was spared execution and essentially served only seven years in prison. We also saw the relatively tiny bridge that the Canadians had been sent to seize.

Our final stop of the day was in the town of Rots (pronounced Rho) and the neighboring village of Le Hamel, where Paul described fights with the Royal Marine commandos and the Canadians against Meyer’s regiment. He described the sad death of a soldier named Jimmy Whitaker and we visited the site of the death.

We had dinner on our own tonight. I have developed a little scratchy throat so I did not go out with the rest of the folks. (This later turned out to be a weeklong head cold.) I looked for a pharmacy for some throat medicine and antihistamines (because my bag has still not arrived), but the day after Easter is a holiday in France and virtually everything was closed In Bayeux. I did find a small sandwich shop and took a panini and some Normandy cider back to my room.

Tuesday, April 2 — Terrain Day

Today we are examining how the different terrains affected parts of the battle, contrasting the relatively flat open spaces west and south of Caen with the bocage country around St-Lô. We started in Norrey-en-Bessin where we had a discussion contrasting the Allied with the German strategy. The Allied commanders were uncertain what the Germans would do, whether they would hit the invasion at the beach, such as at Sicily and Salerno, or sit back and force the Allies to pound them in secure positions away from the beach (and naval gunfire) as they did at Anzio. And of course the Germans were unsure about whether the Normandy invasion was the actual primary invasion effort. We spent the morning following mostly Canadian forces around the battlefield west of Caen; at Norrey there was a monument to the Regina Rifles and the 1st Hussars. The monument listed a large number of names of Canadians killed in this area.

Next was the battle of Mesnil-Patry, where we viewed a wide-open field over a slight rise that had no hedgerows. Paul described it as being similar to the charge of the Light Brigade, one of the worst tank and infantry engagements of the campaign. The Germans deviated from their normal practice of immediate and self-destructive counter attacking, which was something more of the German division should have practiced (but rarely did). Paul described the epic tank engagement at Villers-Bocage where Michael Wittman, renowned panzer ace, destroyed a large number of Allied tanks and artillery, but we did not visit that battlefield.

In Cristot, we visited St-André Church, which had a visibly ruined section. Fighting progressed here June 11–13. In Audrieu, Paul described the murder of numerous Canadian prisoners, again by the 12th SS Panzer Regiment. We drove to a minor high ground, Point 103, and got a good view of St-Pierre, the area known as Lehr Ridge. Here the Panzer Lehr Division, led by Fritz Bayerlein, stood their ground against an attack by the Sherwood Ranger Yeomanry. We drove into the small town to see Paul’s all-time favorite monument, which is hidden away on a side street on the side of a wall: a large number of unit patches carved in stone. Then to a café in town for coffee.

We made a brief stop in the cemetery at Tilley-sur-Seulles and then drove for a view up to Hill 192, an approach that is known as Purple Heart Alley. Now that we are approaching St-Lô, the terrain has changed to hilly bocage country, and we are mostly dealing with US units. We discussed the attack of the US 2nd Infantry Division against the 3rd Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division. The Germans had a unique tactic to deploy. Usually, when faced with an artillery barrage, troops will pull back from their positions and then return when the artillery is finished, which is a great time for us to attack them as they are moving. The parachutists in this case actually advanced forward to avoid the fire, catching the US off guard.

We then proceeded on a 1.5ish-mile hike along Martinville Ridge (the US approach to St-Lô), most of which was narrow muddy lanes in between high hedge rows, to get a close up view of what our soldiers had to experience. Just near St-Lô is the Madeleine Chapel, which is billed as a memorial and not a museum, but all the exhibits, maps, and artifacts say museum to me. Outside is a small memorial to the victims of 9/11, which may be the only one outside of the US, and a companion monument for general memories of worldwide terrorism. Inside we heard about the history of the chapel, which was constructed in 1210 AD, eventually devoted to housing and isolating lepers. The curator used an excellent three-dimensional map board to describe in great detail the liberation of the city by the 29th and 35th Infantry Divisions, opposed by the 352nd Infantry Division and the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Division. He described how Major Tom Howie of the 29th was killed outside where the parking lot stands and how he became endeared to the city as the “Major of St-Lô,” initially retaining some anonymity because pictures of his flag covered body were published in the press before his widow could be notified.

In the city of St-Lô, we visited the church of Ste-Croix, where Howie’s body was first displayed, and a memorial to him at a roundabout. (He was later reinterred to the American cemetery on Omaha Beach.) And Magali, who was born in the city, took us for a tour of the civilian cemetery, where there is a special section of graves for the victims of the evening June 6 Allied bombing of the town. (The Allies attempted to notify the residents to evacuate, but for various reasons none of them got the word. And Magali was skeptical that there was anywhere for them to go.) The city was virtually obliterated and has since been reconstructed in a more modern style.

After a long day, I was really tired out and still suffering from the scratchy throat, so I bowed out of a hosted dinner at a crêpes restaurant. I went back to the hypermarket for cough medicine and some cold cuts for dinner in the room.

Wednesday, April 3 — US Airborne and La Haye de Puis

Some non-agenda news: my bag finally arrived! It traveled from Miami to New York to Paris, sat for two days (Sunday and a holiday), visited two transportation company warehouses, returned to the Paris airport, flew overnight to the Caen airport, visited another warehouse, and then was delivered to the hotel. Whew! Less happy was getting a case of conjunctivitis in one eye and spending three and a half hours at the emergency room for examination and prescriptions of three different drops, which won’t be available until tomorrow. Many thanks to my friend Dave, a physician assistant, and Magali for helping me through the lengthy process.

Today was partially about the 82nd Airborne and the drive across the Cotentin Peninsula as well as a small look at the 101st Airborne. Once again we covered a number of topics and visited places entirely new to me. We started at La Fière, which I had visited in 2019, but we went into a bit more detail this time. The bridge here and another one nearby—the Chef du Pont—were the only ways across the Merderet River, which was massively flooded, and which was critical to linking up to the Utah beachhead. The 505th PIR seized it and defended against a variety of German attacks June 6–9. Paul remarked that the German’s flooding of the area posed as much of a problem for them as for us. He also assured us that estimates of the large number of parachutists drowning in the flooded areas are overblown.

We saw a handsome statue called Iron Mike and Paul told us that a Vietnam veteran was used as the model, which may account for his rather dejected look; oddly, the statue of that veteran is a memorial to Gen. James Gavin of the 82nd. We crossed the street to the manor house, which was there during the battle, but is now a hotel. We heard the story of Cpt. John “Red Dog” Dolan, commanding Company A of the 505th, which captured the Fière bridge. And the heroics of two teams who used bazookas to defeat one approaching Panzer III and three Renault tanks.

We crossed the river to Cauquigny, where the manor was seized by the 2nd battalion of the 507th PIR, commanded by Ltc. Charles Timmes. On June 8, troops of the 1st battalion of the 325th GIR (gliders), captured the causeway to the west of the bridge, but they could not advance further because of enemy resistance. 1LT John Marr found a hidden ford and attempted to seize the causeway from the rear, but the attack was not successful. On June 9, another attempt was made and PFC Charles DeGlopper received a Medal of Honor for his actions in the assault.

We drove to Doville and observed the five major hills in the area, which were being approached by the Das Reich division as the 82nd was moving southwest. The 82nd was in the middle of a leadership crisis because it had suffered staggering losses on the way to this area, including many company and battalion officers. We stopped at Hill 95, which was once used by the Roman army. The Germans launched three counterattacks from this area. The 82nd was eventually withdrawn and sent back to England for refitting.

Next was nearby La Haye du Puits, where we saw a monument to the 79th Infantry Division. We discussed the fighting on Mount Castre between the 90th Infantry Division and the 712th tank battalion against the Fallschirmjägers. The journalist Andy Rooney likened this battle to the severity of Iwo Jima.

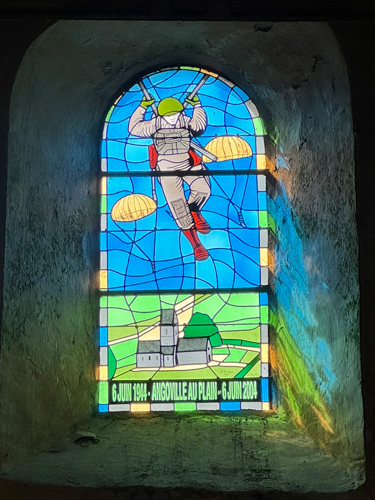

Heading back to the east, we drove to Angoville-au-Plain. The 101st Airborne Division had no particular objectives in this area beyond killing Germans where they found them. The 700-year-old chapel, Église St-Côme et St-Damien, was taken over by two medics, Bob Wright and Ken Moore, and despite having only the minimal field medicine training, they treated scores of patients, using the pews as beds, where blood staining is still apparent. Paul told us a number of touching anecdotes, which can be read in his book Angels of Mercy.

Our final stop of the day was outside of Carentan, where instead of recounting the 506th PIR actions that were in the Band of Brothers, we looked at the action on the highway known as Purple Heart Lane, where the 3rd battalion of the 502nd lost 60% of their strength in casualties.

As I mentioned above, I spent all evening at the hospital emergency room, so no dinner with the group. All the rest of them had a convivial time at a local English style pub.

Thursday, April 4 — Operations Cobra and Lüttich

This morning our van stopped at a pharmacy so that I could get three prescription droplets for my eye, which was surprisingly fast (and cheap) in comparison to US pharmacies. Later in the morning I realized that the infection has spread to the other eye, which is apparently pretty common, but at least I have medicine to treat both of them. And I did notice some improvements during the day.

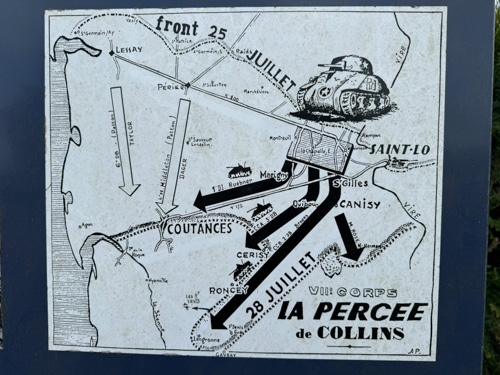

We drove west to Périers and saw the monument of the 90th Infantry Division, the “Tough Ombres.” [sic] We discussed the plans for Cobra (the concentrated bombing by the heavy bombers followed by a breakout) and talked about the enormous impact on the Germans. Our troops suffered 460 friendly fire casualties, but nothing like the destruction laid down on the German troops, primarily from the Panzer Lehr Division.

We next went to the small town of La Chapelle-Enjuger on Highway D900, which was the exact spot of the rectangular bombardment area. Paul described the routes of the US VII and VIII Corps, and how the British operation Bluecoat proceeded just to the east on the same southerly axis of advance. In the town of Marigny, we visited a cemetery that was originally a temporary one for US soldiers, but was later converted to a German cemetery, interring 11,000 soldiers.

Just below the bombardment rectangle, we observed Les Mesnil-Ames Château, which was the headquarters for Fritz Bayerlein, commander of the Panzer Lehr, and we discussed the enormous German morale change caused by the bombardment. Many no longer believed that a victory in the west was possible. At St-Denis-de-Gast, we stopped at a road junction and looked at a highway on which hundreds of withdrawing German vehicles had been annihilated by Allied air support. Paul described a situation called cab rank air support, where fighters from Normandy airfields would ascend and circle until they were directed to specific targets.

The most important town in this region was Avranches with its strategic crossroads, and being the gateway to Brittany. We went to the Château d’Avranches and climbed to the top to see a stunning view, including Mont St-Michel way in the distance off the coast. Paul described how Omar Bradley had put George Patton in temporary command of the VIII Corps, which raced south to capture the city. (On August 1 Patton would command the newly activated Third Army, including that corps.)

We had lunch in an old-fashioned French bistro, and then walked over to the large square that contained monuments to Patton as well as a number of businesses with the Patton name, such as a driving school. There is a very large monument commemorating the liberation of the town and all of the subordinate corps to the Third Army, as well as a bronze bust of Patton in a tanker uniform that he designed, and an M4A4T(75) tank. This stop was the only one today that I had seen previously.

We drove to Le Pont de Pontaubault on the Sélune River, south of Avranches, where seven US divisions crossed in 72 hours. Then east to Mortain, where Hitler ordered a fruitless counterattack, Operation Lüttich, sending parts of five armored divisions (but numerically less than three) in an attempt to drive the US back to Avranches (at which point it was completely unclear what would have been accomplished). In the hamlet of Neufberg, we talked near an abandoned train station about the northern part of the German attack on August 6. Then we went to Hill 314 (Montjoie), where the 30th Infantry Division withstood the southern part of the German attack, lasting from August 9 to August 13, while being surrounded. The 370 men on the hill rejected a German surrender demand. With these failures, German troops started withdrawing to the east, which led to the Falaise Pocket operation, to be discussed tomorrow.

Quite a lot of driving today. Back at the hotel, we had a free evening, and since I am still feeling somewhat under the weather, I got a room service charcuterie plate and worked in my room.

Friday, April 5 — Falaise Pocket

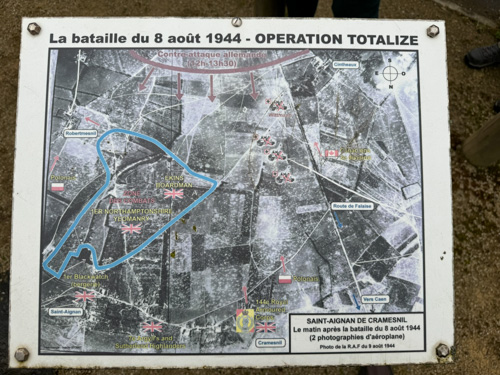

We started south of Caen at Saint-Aignan-de-Cramesnil to see the monument to the 1st Northamptonshire Yeomanry, which liberated the town on August 8 as part of Operation Totalize. Totalize and Tractable were operations launched in parallel with the Cobra breakout by the Brits, Canadians, and Poles. We studied some aerial photos that show the landscape here completely overwhelmed by artillery craters. German Panzer ace Michael Wittman launched a really stupid charge here with four Tiger I tanks; all were killed. (I forgot to mention that on an earlier day Paul described a meeting he had with Whitman‘s wife and she was as much of a racist Nazi as her husband had been.)

Next was the town of Falaise, which was the home of William the Conqueror and we noticed a good deal of bullet damage on his castle. Falaise gives its name to the operation we are examining today, but all of the interesting action occurred a good deal east of here. We spent the next several hours traversing three towns in a 7 km line running northwest to southeast: Trun, St-Lambert-sur-Dive, and Chambois. They are all on the Dive River, which in this area is only a minor stream, but nevertheless an obstacle to vehicle traffic because of its steep banks. There are only four bridges and one ford in this area that would allow the Germans to escape the envelopment the Allies planned.

We went to a heightened observation point outside St-Lambert and got a good geographic overview of this rather small battlefield. Then we drove into town to a monument for Maj. David Currie of the 29th Canadian Armoured Reconnaissance Regiment and discussed his exploits defending the town for a few days. We also visited his position on Hill 117, where he ordered a Sherman machine gun charge across the field that both he and the enemy occupied. (His men were warned to dig in.) Throughout this campaign his unit had 50% casualties and he was awarded the Victoria Cross.

At the main stone bridge across the Dive, we saw where hastily arrived 17-pounder towed antitank guns destroyed a number of German vehicles. In the Chambois hamlet of Moissy we visited the Gué (ford) de Moissy, which was the central starting point for the famous Couloir de la Mort (Corridor of Death). In Chambois we ate a bag lunch and saw a small castle and discussed how the Canadians, Polish 1st Armored, and US 90th Infantry Division met up, closing the gap that allowed 50,000 Germans to escape.

We drove to Caudehard, where we visited Hill 262N, where a number of the Polish troops were stationed. Paul described a battle in which over 70 tanks fought each other at arm’s length in a modest field. Then we drove the short distance to Hill 262S, Mont Ormel, which I had visited in 2019.

The memorial at Montormel has on display the ubiquitous M4A1 and an M8 Greyhound armored scout car. There is also an excellent small museum that covers a lot of the Normandy Campaign. We stood before a large panoramic window that had a wide view of the Dive Valley and the museum director gave a good, albeit heavily accented, description of the battle, including the German counterattacks against Mont-Ormel and Bousjos hill. The destruction of the area and the German forces was awesome. He said it took 20 years to clean up the mess. For weeks, the skies were black with flies and the ground looked like there were patches of snow—maggots. He said the area looked like the aftermath of the Sommes and Verdun. In addition to this lecture, we saw a very elaborate animated map display and a relatively short film about the battle.

We made some brief stops in the town of Vimontier. First was a derelict Tiger I tank on display that had been scuttled by its crew and rolled down a hill, to be recovered 30 years later. It’s in poor shape with some missing pieces and a large crack in the turret, but it’s always impressive to see one of these giant vehicles. Then we found the road on which Erwin Rommel’s staff car was attacked by a Spitfire on July 17, causing severe injuries that were handled (temporarily, at least) by an equine veterinarian nearby. Rommel was out of action as a combat commander and later was accused of abetting the Hitler assassination conspiracy, which led to his coerced suicide.

Our final stop of the day was near the town of Langannerie, the Polish military cemetery, which we felt was appropriate given our examination of Polish heroism during the day today. We had a farewell dinner at a nice Bayeux restaurant, La Table du Terroir.

Saturday, April 6 — Cemeteries and Return to Paris

We made a bonus stop in Crépon, straddling the rear of Gold and Juno beaches, to visit the Green Howards monument. Paul described the exploits of Stanley Hollis, who received the Victoria Cross, a feat that was difficult at the time, according to him, because the British Army had temporarily run out of the special bronze material necessary for issuing the metals. Then to Ver-sur-Mer to visit the relatively new British Normandy Memorial overlooking Gold Beach. It had only opened in 2021 for the 77th anniversary of the battle, right in the middle of the Covid pandemic. It is a very impressive monument spread over a number of acres, including high-level descriptions of the Normandy campaign—there are six huge marble slabs representing each stage of the campaign, although it is text based without maps—as well as a large collection of marble posts listing information about each person (those under British command) killed during the campaign. I found it a little clumsy that the names of the dead are sorted by date rather than alphabetically, but it is all quite beautiful.

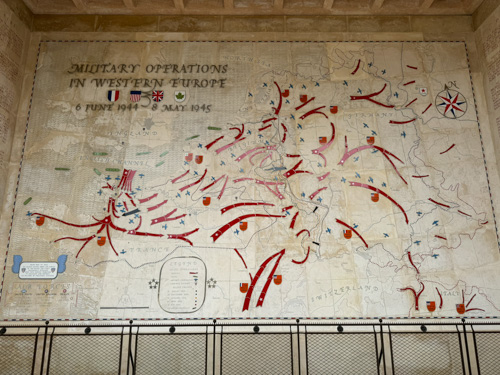

Our final stop of the week was in Colleville, the American cemetery, overlooking the Easy Red Beach. I had dismissed this beforehand because I had visited the cemetery over a full day in 2019, but I was certainly wrong. I found many things were dramatically different than the set up I attended for the 75th anniversary. There was no giant stage, so we were able to enter the Garden of the Missing that it had previously blocked, a lovely area listing those men, along with the typically excellent, stupendous campaign maps that American European cemeteries like. In front of the stage there is a large reflecting pool, which had been covered over and used for seating in 2019. And there was a large and modern visitor center with an excellent series of exhibits about the campaign. About the only negative thing I can say is that the cemetery policy has changed and you can no longer wander among the graves. Relatives can get escorted if they wish to visit a specific grave and decorate it with flowers (although Magali told us they are discouraging flowers because it is too much work for the gardeners; I did notice that the gardeners also did not have time to weed out the dandelions all over the gravesites). Mag escorted us around and pointed out some important graves that were visible from the paths, such as Theodore Roosevelt, Jr, one of three in the group who received the Medal of Honor.

I had an outstanding tour with Paul and Magali, one of my top military history tours of all time. The content was excellent and the bonus was that there was very little overlap from tours I had taken previously. We really dug deep into aspects of the campaign that were unknown to me, but very interesting and insightful. It was also fortunate that the group was so small because we fit into a van that had access to a lot of places a larger bus could not. They have been talking about a part two, building on this experience, but with further new material, sometime in 2025, which I will definitely try to attend if my schedule permits.

The rest of this page covers activities not included in the tour, so WW2 folks can bail out now…

I drove my rental car back to Charles de Gaulle airport and checked into the Pullman Hotel, which I have stayed in previously, right next to the train station in Terminal 3. I cannot say that a combination of airport signage and Google or Apple Maps make it very easy to find the rental car return. I had to hold my breath when I filled up this relatively small hybrid car with over $100 in gas!

Sunday, April 7 — Paris

The reason I am still in Paris is as a padding day, trying to guard against delays along the way that might cause me to miss an international flight. (My original itinerary was to take the train and it was quite difficult to find times that had not been booked.) I took the RER train from across the street from the Pullman Hotel and reached Paris (Chatellets Les Halles station) in about 30 minutes. Since I was early, I had a nice continental breakfast at a café, and then I walked to the Louvre Museum. Although it was a short walk, it was challenging because the Paris marathon started that morning and thousands of runners were looping around the Louvre at about mile 4, so still pretty fast, and I had to weave my way in between them to cross two streets.

I had booked a three hour guided tour of the Louvre and it was quite satisfactory, hitting all of the highlights including the Mona Lisa, Venus de Milo, Winged Victory of Samothrace, and lots more, led by a Jordanian man with art history credentials. I don’t recall going to the Louvre since 1977 so I experienced big architectural changes that came about in the 1980s with the I.M. Pei redesign. Very beautiful. I did not bother captioning the photos I took below, and it is certainly not an exhaustive reckoning of the Louvre collection (which I think is about 1/2 million objects).

I walked about a mile and a half to the Army Museum at Les Invalides, stopping along the way for a light lunch at a sidewalk café. I had one heckuva time finding it, as Google Maps’ walking directions kept trying to route me through locked iron gates and moats (yes, really). I found the museum to be a bit weak. I only wandered through the world war exhibits, and I have certainly been to better explanations of the two wars. Although you might expect World War II to be somewhat sketchy based on the limited French participation, World War I was also under played. I did enjoy seeing a French armored vehicle that was new to me (a Renault 31R UE), but if you are interested in French tanks, a trip to Saumur is warranted. See here. I did not spend the time to visit the Napoleonic or other eras, so perhaps they are superior. Then a 14-stop subway ride and the RER—both rides standing room only—back to CDG for a quiet dinner in the hotel.

Monday, April 8 — Home

I flew United back and crossed my fingers, which apparently worked. There were no delays, failures, or lost luggage. I got a couple of nice photos of San Francisco and the Bay as I returned.