Hal Jespersen’s UK Mighty Eighth Air Force Tour, September 2023

This is my (Hal’s) report of a trip sponsored by the National World War II Museum to examine the history and some of the sites of the US "Mighty Eighth" Air Force in England. I have been trying to emphasize more World War II travel and this is my first excursion with the museum. I have arranged this report so that the actual museum tour is in one page, and activities before and after are on a separate page, as follows:

- Activities before and after the Museum tour.

- Mighty Eighth Air Force tour. (This page)

Wednesday, September 6 — to Cambridge

I met the tour group at a different airport hotel from the one I booked, which involved a lot of walking and traveling the (free) London underground from terminal two to terminal five, a journey that surprisingly took 45 minutes. We have only 15 participant, so lots of room on the bus. The staff is our tour manager, Naomi Briggs, and historian Bob Shaw, a former British Army officer (with a colorful history that included a lot of explosive ordnance disposal and intelligence work), but one who knows quite a lot about aviation matters and many other subjects. On the bus, Bob gave us a very concise explanation of the Battle of Britain, its leadership, and its two primary fighter aircraft. I subsequently found out that Bob had intended to include a comparable overview of the American campaigns in the air war, but ran out of time.

Our first stop was at Bentley Priory, originally founded by monks in the 13th century (although the current building was built in the 18th), the headquarters of RAF Fighter Command. We examined two fighter replicas posting guard out front. Bob described the characteristics of the Hurricane and Spitfire; the latter is the famous one, but the former was actually more prominent in the Battle of Britain, with more kills; because it was a bit slower, the Hurricanes focused on the relatively vulnerable German bombers instead of their fighter escorts.

We had a tour of the museum, starting with a bio of Air Chief Marshall Hugh Dowding. There was an interesting multimedia film about the battle that was projected onto the front of Dowding’s office. We heard brief summaries of a number of fighter pilots. We toured a reproduction of the Filter Room, where all the intel from the coastal radars was sorted. And we went into a large room where there was an experimental Operations Room, processing both radar data and sightings from the Observation Corps, and dispatching and tracking fighter squadrons; a small model illustrated what the room would have looked like. Both of these processing rooms were actually housed in a bunker nearby, which we were not able to visit. We concluded with a light lunch in the café.

We bused about an hour or so to Cambridge and checked into the Gonville Hotel, which is small but very elegant. I took a stroll downtown on the main drag, and I found the commercial area to be a bit shabby—a walking tour later this week revealed a lot of nicer and more historic areas. Dinner was in the hotel restaurant, which was excellent. During brief introductory remarks from each participant, I learned that most of the people on the tour had actually signed up via the US Air Force Academy Graduates Association or the comparable group for West Point. Only a couple of us had signed up directly with the museum.

Thursday, September 7 — Duxford

After a very sumptuous breakfast, we started with a PowerPoint presentation by Bob: the Development of Air Power. Then we bused about 30 minutes to Duxford Airfield, home to both RAF and American fighters during the war, where the Imperial War Museum now has a giant installation. We toured unguided through a number of large buildings/hangars. I started with the American building, which had planes squeezed in like a complex jigsaw puzzle. They had all the WW II favorites, as well as more recent ones, such as an SR-71, an A-10, and the only B-52 I have ever seen inside a building. A monster. Their B-25 Mitchell was the one Joseph Heller flew in Italy, inspiring him to write Catch 22. There was an unpainted B-24 Liberator, all shiny aluminum, but it was so squeezed in that I could not get a reasonable photograph.

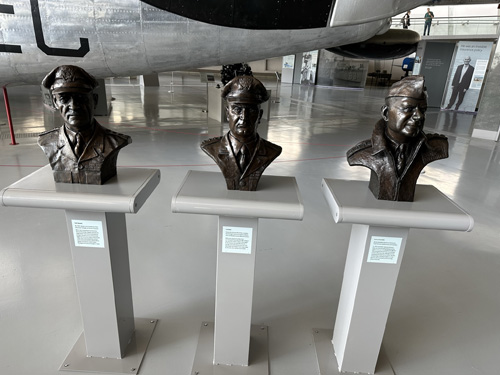

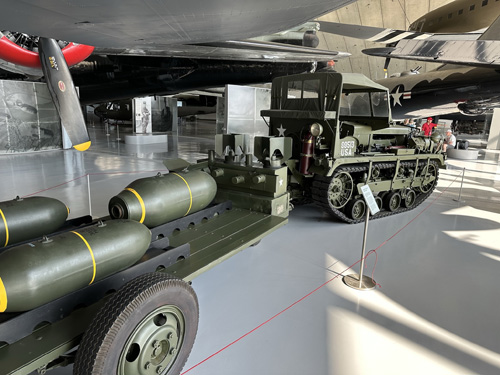

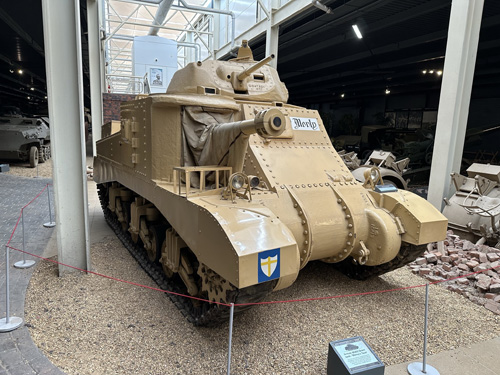

The next building concerned land warfare and they had a number of tanks, vehicles, and artillery pieces. I only photographed a few of the interesting tanks. It was sort of an odd display because the building was rather dark and all of the vehicles were displayed amidst ruined buildings, rubble, and camouflage gear, trying to simulate a combat environment. There was a Tiger I, but it was only a replica. There were British, German, and Soviet tanks from World War II and the Cold War, but I did not see any American (other than an M3 Grant that supposedly belonged to Montgomery in North Africa). Next was a building with Battle of Britain aircraft and a companion building that represented the Duxford sector control operations room, similar to but smaller than the Bentley one yesterday. On outside display were a number of civilian airliners as well as a beautiful B-17, which was carrying two identities. One side had a very risqué naked lady painted on the nose and the name Sally B (which I learned was the correct name) and the other a replica of the Memphis Belle nose paint. The actual Memphis Belle is preserved in the US Air Force Museum in Ohio. There is also a Concorde owned by the museum, but it was in a building that I somehow overlooked.

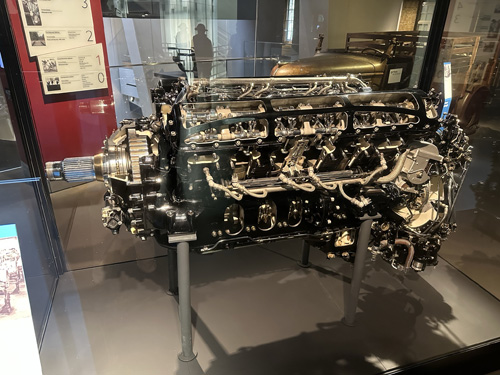

We had lunch on our own and I selected a delicious sausage roll. Then we met up again and visited the Aircraft Restoration Company, who put on a dog fighting demonstration for us using a Spitfire (one of the relatively rare two seaters, which they normally rent out at astronomical prices for joyride flights) and a Messerschmitt Bf-109 (which was actually a Spanish version of the plane, built in 1959, with a Merlin engine, which appeared in the film Battle of Britain). The maneuvers were rather impressive, including one in which a plane would fly vertically, stall out, and then swoop down around the enemy. I attempted to video pieces of it, but had a lot of difficulty actually seeing the view finder screen on the phone in the bright sunshine, so I did not always keep the planes in frame. (It is amusing to see how the video frame rate affects the appearance of the rotating propellers.) Today was another hot one in the upper 80s, and we viewed the hour long demonstration in the direct sunshine. After the planes landed, the two pilots, Mo and Rats (Messerschmitt and Spitfire, respectively), came to answer questions. One described the Messerschmitt 109 as “an angry hornet in a jar,” with characteristics that made it very dangerous to take off or land. He said that 33,000 of these planes were destroyed in the war, and 11,000 of them were lost in takeoffs and landings, not combat. I was interested to learn that Rats, a former RAF officer, is currently a pilot with Virgin Atlantic. Sort of a Busman’s Holiday.

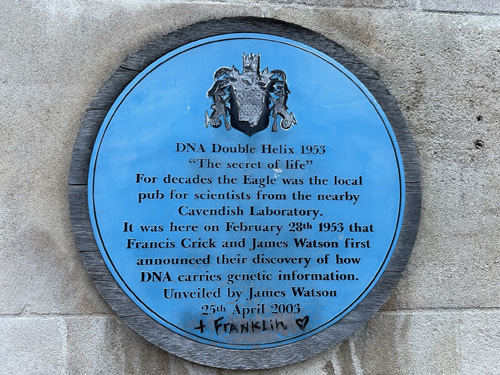

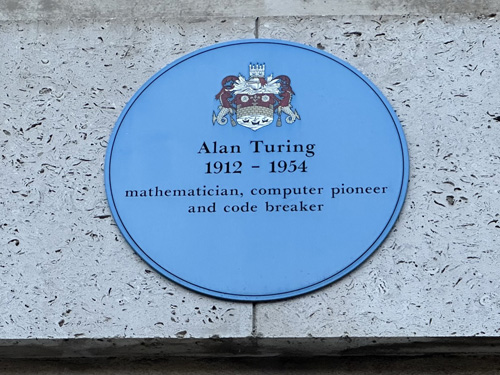

After a three-hour break at the hotel, we met for dinner at the historic Eagle Pub, established in the 14th century, and one of the main venues for RAF officers to relax during the war. The walls and ceiling are completely plastered over in military unit patches and graffiti. Of historical note, Krick and Watson announced their discovery of DNA at the pub. And within one block, there is a historical plaque recognizing Alan Turing. There is also an extremely odd clock showing time being consumed by a monstrous grasshopper, the gift of a donor who spent over $1 million building it. Dinner was steak and ale pie, which was excellent.

Friday, September 8 — Cambridge and Bury St. Edmunds

We bused a couple of miles through Cambridge and started a walking tour with a very knowledgeable guide, Johnnie. I realized to my chagrin that I left my hat in the hotel room and was ready walk back a mile or so and retrieve it, but Bob graciously insisted that he could walk over and get it for me so I wouldn’t miss any of the tour or lunch. Kudos to Bob for a great favor.

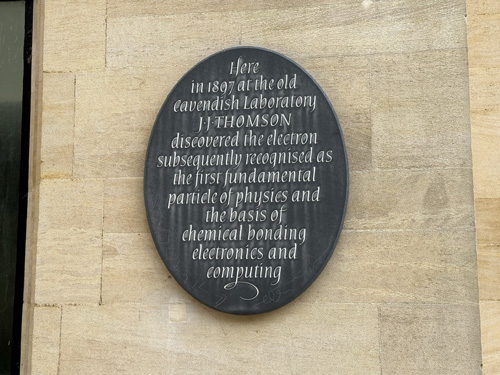

Our tour started at Queens’ College (NB the punctuation—many queens and other women were responsible for founding the various colleges) and went to Peter House (named after St. Peter), founded in 1284. Johnnie gave us a brief history of Great Britain and the university, which was founded by Oxford professors who were put off by some of their colleagues being burned at the stake for a murder that they did not commit. We strolled down Little St. Mary’s Lane and noted #6, where Stephen Hawking lived before he was disabled. Next was Pembroke College, designed by Christopher Wren, and hosted William Pitt and Ray Dolby. And the original site of historic Cavendish Laboratory, which I consider the birthplace of the atomic age. (I visited the current Cavendish Laboratory on the West Campus in my post-tour travelogue.)

We stopped at Corpus Christi College, which coincidentally owns the Eagle Pub we ate in last night. Across the street was St. Bene’t’s chapel. Its tower was built in 1020 by the Saxons, the oldest building in Cambridge. Then King’s College, founded in 1441. The magnificent chapel, more like a cathedral, took 100 years to build during the War of the Roses, but was finally finished by Henry VIII. Unfortunately it was being restored today, covered with scaffolding, and we could not go inside. We passed by the Senate House and then stopped briefly at a large square with a seven-day farmers market, next to Great Saint Mary’s Church. We walked through a large attractive park on the river, and had lunch at a restaurant called Millwork, and once again had an excellent meal. (Note: I returned to Cambridge the following week and there are more photographs here.)

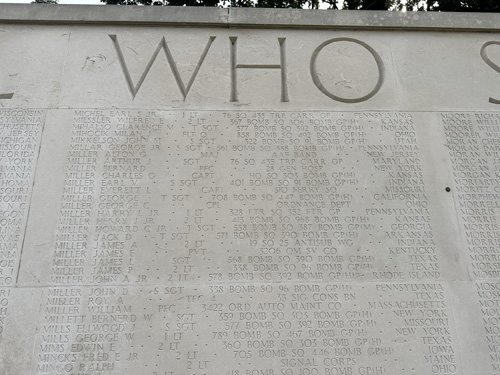

We bused to the Cambridge American Cemetery, where 3,812 are buried and 5,127 unknowns are listed on a long marble wall. The former include a large number of UK training accidents, like Slapton Sands in 1944. The latter are mostly airmen lost on missions and seamen from the Battle of the Atlantic. I found Major Glenn Miller’s name in the list. The chapel has a stupendous map of Europe and the Mediterranean, which is beautifully designed. Our visit was marred by an accident, which caused us to postpone a planned memorial wreath laying. One of our ladies tripped and conked her head on the pavement, requiring help from one of our group, a doctor, and she was evacuated by an ambulance. The hospital discharged her at 2 AM and she returned to the hotel; she and her daughter ended up missing a couple of days of the tour.

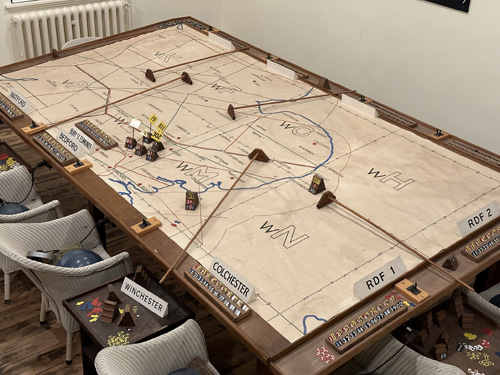

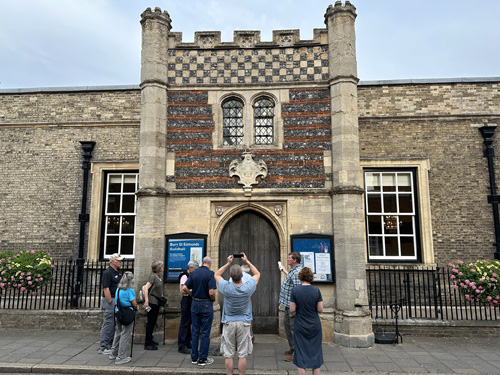

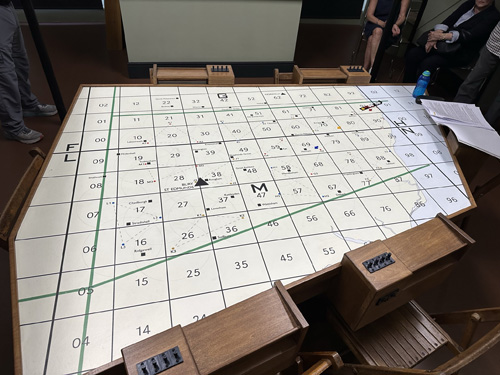

We checked into the Angel Hotel in Bury St. Edmunds, about 45 minutes from Cambridge. It’s a very cute little town. We took a walk to the Guildhall to visit the Royal Observer Corps Headquarters. They gave us a fully detailed explanation of how the visual observations in the field were accumulated over dedicated telephone lines and sent up to Bentley. Then a decent dinner in the hotel. The hotel is typically old English, with unpredictable wandering floor plans, funky electrical systems, and an old fashioned bath, but quiet and reasonably comfortable.

Saturday, September 9 — Thorpe Abbots and Horham

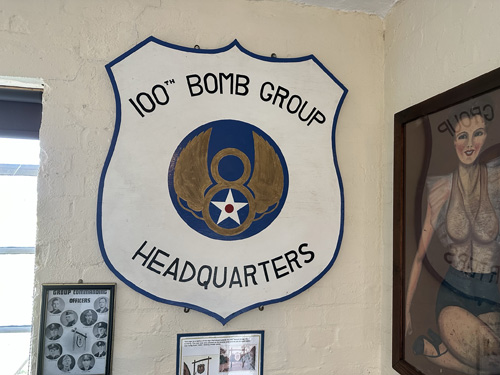

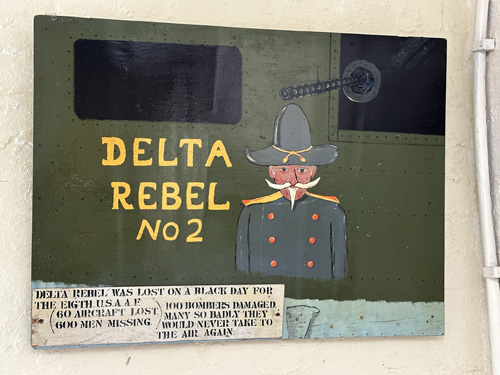

We bused about 45 minutes on mostly country roads to Thorpe Abbots, home of the 100th Bombardment Group, the “Bloody One Hundredth.” It was not in fact the BG that had the deadliest record of losses, but was given that nickname after two back to back disastrous missions to Bremen and Münster; in the latter, 13 planes went on the mission and only one returned. Different docents told us different casualty figures, but it seems that about 757 were killed in action. This BG is the primary subject of the upcoming Tom Hanks, Steven Spielberg Apple TV+ miniseries, Masters of the Air, based on the book of the same name by Donald Miller, which I read prior to joining the tour. Our tour guide Bob Shaw was involved in boot camp training the actors for this series.

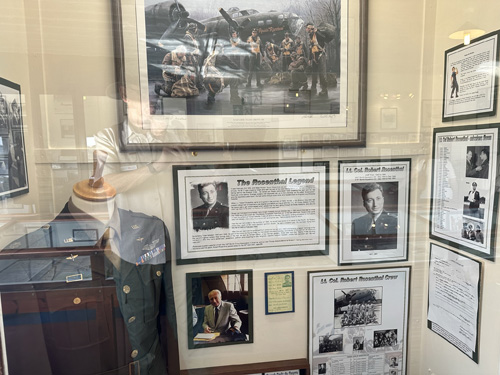

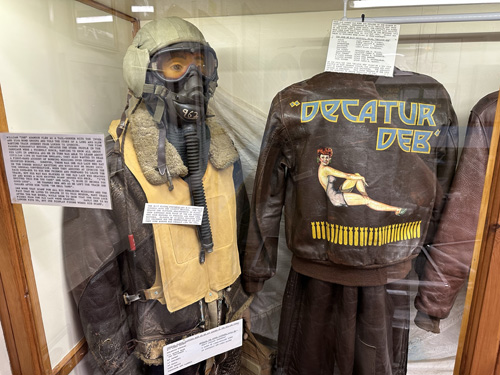

The main runway has been plowed over and sugar beets have been planted, but we drove in on a perimeter road/taxiway to a small collection of buildings including a control tower and a Nissen (Quonset) hut that have been restored to their wartime appearance. We were met by Ron Bagley, who was the son of a local resident and heard many stories from his family about the airman at the base. There is a small museum shared between the hut and the tower. There is a lot of emphasis on interesting individuals who served in the BG, displaying their records, patches, metals, and personal artifacts. One such person, whom I believe is going to be included in the HBO series, is LTC Robert “Rosie” Rosenthal, commander of the 350th Bomb Squadron, the most decorated man in the Eighth Air Force, who survived 52 missions. The museum displays go into an extraordinary amount of detail about all of the flight crews, their airplanes, and how each of their important missions were organized and executed.

We had a buffet lunch catered by a local pub and then as our bus departed, we took a guided tour with a historian who showed us around all of the areas of the large base, including hard stands, former hangars, and barracks buildings. Virtually nothing is actually left and most of these areas have been forested over in the 80 years since, but it was good to get a sense of the size and layout. I was interested to hear that Glenn Miller performed here once in one of the hangars, T2.

But there was more Glenn Miller to come, because we took another 30 minute bus ride to the village of Horham, home of the 95th Bombardment Group. Miller’s orchestra performed, along with Bing Crosby and Dinah Shore, in August 1944 on the occasion of the 200th mission performed by the 95th. I talked to a man who was seven years old at the time and heard the concert. The 95th has the distinction of flying the first mission over Berlin and received three presidential unit citations, more than any other BG in the Eighth Air Force. They also have a decent museum with a lot of detail about missions, personnel, etc., but the format is completely different because it is housed in a former NCO club that is called the Red Feather Club, and it includes a bar and dance floor.

As a really special treat, our group was entertained by a big band of professional musicians dressed up in Eighth Air Force uniforms. There were only eight instruments and one young attractive female vocalist, but the band was really fabulous, and since I love big band music of the 1940s, I was completely blown away by the experience. They did quite a few numbers, including hits by Miller, Goodman, Duke Ellington, and Ella Fitzgerald, although I was disappointed that they did not play my favorite, Moonlight Serenade. There were also a few couples dancing away, and some of our group joined in, but I am too shy and uncoordinated (and wearing hiking boots) to dance myself. And once again it was unseasonably hot today, which played havoc with the interior of the Quonset hut. We concluded with afternoon tea and a ride back to the hotel.

Dinner was on our own tonight and I tagged along with a group that ate downtown at a place called the Corn Exchange. It’s like a gigantic pub in a historic building, with all the typical pub beers and casual foods.

Sunday, September 9 — Parham

We bused for an hour east to the village of Parham, where the Framlingham Air Station #153 has another small museum. This one commemorates the 390th Bombardment Group, like the two previous groups part of the 13th Combat Bombardment Wing, 3rd Bomb Division. (The 95th, which we visited at Horham, actually preceded the 390th here with a stay of two months.) The 390th had the reputation as the most accurate bombers of all the BGs, with casualties just a bit shy of the Bloody Hundredth—742 killed, 731 captured. We were greeted by the head of the restoration committee and went into their restored Nissan hut (which the Brits describe as being roofed by “wriggly tin”).

The museum, which also includes a restored control tower, was pretty similar to the previous ones, but they had a lot more equipment artifacts, both intact and horribly mangled in crashes. There is a beautiful B-17 model at 1/10th scale, the Lady Velma. There is a data board about Sgt. Hewitt “Buck” Dunn, who holds the distinction of completing 104 missions! And lots of photos and descriptions of local plane crashes. A very impressive collection.

We were summoned outside for a memorial wreath laying ceremony. The WW II Museum intended for us to place the wreath at the Cambridge American Cemetery, but because of the medical emergency that day, we postponed until today. I then retired to a portion of the museum devoted to the British Resistance Organization, aka Auxiliary Units, which is an organization that remained a secret until years after the war and I had never heard of. Wikipedia has a summary article about these civilians trained to be guerrilla fighters in the case of a German invasion of England, and it all looked very interesting, including an informative five minute film, but all of a sudden the bus departure time was moved up and it was visit interruptus for me. As we departed, we got another guided tour around the large expanse of the air station. There are more building surviving than in the previous BG, including a restored hangar, one headquarters building, and a few Nissen huts that seemed to be in use as farm buildings.

Driving back to the outskirts of Bury St. Edmunds, we had Sunday lunch at the Ravenwood Hall hotel, an elegant old place in the woods. Sunday lunch included roast beef and Yorkshire pudding, and all of the courses and accompaniments were quite delicious. When we returned to the hotel Bob gave us a presentation about MI9, the British organization that managed escape and evasion for the RAF in Europe. (I have always heard of MI5 and MI6, but Bob told us that there are MI1 through 11B, apparently corresponding to room numbers in the headquarters.)

Dinner was on our own again and I joined a group that went to a nice French brasserie near the hotel and then returned to the hotel bar for “a pint.”

Monday, September 11 — Bletchley Park and London

We checked out of the Angel and bused 90 minutes to Milton Keynes for a visit to Bletchley Park. This was actually my third visit since 2019, so I was unconcerned that inadequate time was allocated. We had a one hour tour with a rather droll guide named Mike Saunders, but it was quite superficial, not entering any of the hut exhibits, for instance. Then we had but one hour to eat lunch and see whatever else we could squeeze in. I made a brief return visit to hut 11/11A to see the replica Bombe demo again. I did not bother with a lot of photographs for this return visit. I will point you to my previous visit for additional details.

Then another 90 minutes on the bus to reach central London and tour the HMS Belfast. I can’t say this was too interesting or relevant at all, and I had to devote a lot of attention assuring I did not hit my head on the very low clearances or kill myself on the super steep ladders between the decks.

We then drove another 30 minutes to our final hotel, the Rubens at the Palace, which is literally across the street from Buckingham Palace's Mews. A very nice room, where I was greeted with a handwritten note from the staff, a chocolate chip cookie, a stylized view of the London skyline in powdered sugar, and a macaron that had our museum logo imprinted on it. During the war it was the headquarters of the Polish army and Charles de Gaulle visited.

It was dinner on our own again tonight. A group of us joined Bob for dinner and another pint at his Army club, the Union Jack, near Victoria Station. It was interesting to see lists of, and some photos of, the awardees of the Victoria Cross (equivalent to our Medal of Honor) and the George Cross (for valor not directly connected to action against the enemy).

Tuesday, September 12 — London

I usually don’t eat breakfast because of my intermittent fasting regime, but today I strayed and had the full English breakfast in the fancy hotel restaurant. Pretty nice, but at a list price of £45, it would not be something I’d order if it weren’t included in the room package.

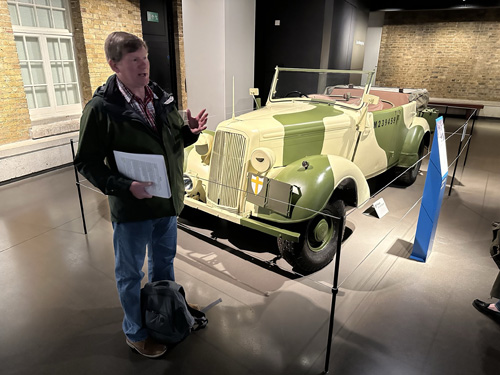

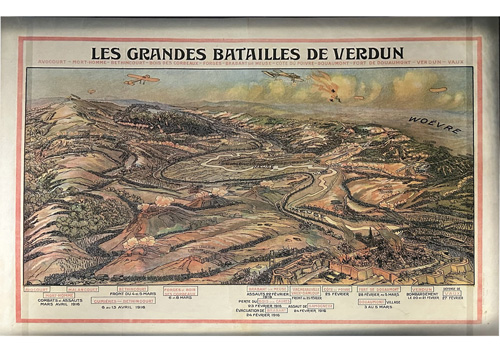

We bused to the Imperial War Museum. Bob toured around the WWII floor with us and offered lots of interesting commentary. Then let loose, I headed down to the WWI floor and was very impressed with the cutting edge visual design and all of the beautifully preserved artifacts; a bit light on battle maps and details, though. The WWII floor is a pale comparison in terms of explanatory material rather than just large weapons and vehicles. Bob told us that current school children receive almost no instruction on the second world war, with testing preparation emphasis on the first.

We walked down the street to the Three Stags pub where most of the folks had fish and chips, but since we had that last night at the Union Jack, the pub accommodated me with a lamb burger. Then off to St. Clement Danes Church, the official church of the RAF. It was originally there in the 9th century, named after the patron saint of mariners, was absorbed by the Danish Vikings, burned in the Great Fire, rebuilt by Christopher Wren, and destroyed in the Blitz. After the war the RAF restored it. It contains many memorials to units and individuals, including books with casualty lists and almost 900 squadron-level emblems/badges on the floor, carved from Welsh slate. There is a small section commemorating the American contribution to the air war, framed by a portion of the Gettysburg Address! In front of the church are two large statues of Hugh Dowding and (the controversial) Bomber Harris.

Our final stop was at Whitehall for the Churchill (Cabinet) War Rooms. This was my third visit, but since the previous one in 2019, they seem to have improved the display infrastructure quite a bit and they now have an audio device to carry around and explain stations. All the underground rooms seem about the same as I recalled, and remain quite interesting, but the very extensive Churchill biography section seems a bit improved. It is unfortunate that the room most interesting to me, the map room, is very difficult to examine or photograph in detail.

We concluded the day with a reception and farewell dinner at the hotel. (Some of the previous versions of this tour had the dinner catered at the Churchill War Rooms, but apparently it was already booked by another group this time.) All in all I have had an excellent time on this tour and commend Naomi and Bob for their admirable performances. It was great to learn about the sacrifices of our brave airmen and women and even the places that I visited for a second or third time were interesting. And the accommodations and logistics were first rate. I may consider a future tour with the National World War II Museum.

Go to my pre- and post-tour page to read about my visits to Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory and Bletchley's National Museum of Computing.