Hal Jespersen's World War I Tour, November 2023, Part 2

This is my (Hal’s) report on my trip to Belgium and France for a tour of the World War I Western Front, hosted by Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. It is my third tour with Ambrose, the first being the 75th anniversary of D-Day in 2019, followed by Patton’s advance across France and Belgium to Germany, then the Italian Campaign from Sicily to Rome. Those travelogues are here and here. Because this report is so large, I have broken it into three parts:

Contents – Part 2

← Part 1: London, Brussels, Waterloo, Ypres, Arras

→ Part 3: Château Thierry, Belleau Woods, Verdun, Meuse–Argonne, Meaux, Paris

Friday, November 3 — Arras, Vimy Ridge, Cambrai

We started at Notre Dame de Lorette, the world’s largest French cemetery with over 40,000 burials. About 20,000 are unknowns and there are also ashes from concentration camps. There is a large chapel and a giant monument, the Lantern of the Dead, but the latter was encased in scaffolding, and the whole facility was locked. Four battles were fought in this area, including three at Artois, and together they suffered casualties about the same as Verdun. Next door is the NDL Memorial, which is a stupendous oval structure that has inscribed the names of 580,000 people dead in northern France, alphabetically without regard to units or nationalities. There are two men named Jespersen on the list, no known relation.

Next was a tiny cemetery that contained Czechoslovak graves. Chris explained that there was no such country then, being only part of Austro-Hungary, but these were volunteers recruited from all over the world who hoped their service would help promote eventual independence. Across the street is a Polish cemetery.

Vimy Ridge, part of the battle of Arras, was the first time four Canadian divisions fought together, and is seminal event in Canadian history. The ridge had been held by the Germans since October 1914, but on April 9, 1917, the attack by 170,000 men over a four mile front got it back, losing about 10,500 casualties. As with Arras, there were 10 km of tunnels to provide some surprise access to the German lines, but there were also advances in rolling artillery barrage techniques. We were led by a young Canadian named Felix through a preserved tunnel and an observation trench, and also roamed around some of the German trench line, only yards away from the Canadians.

Next we visited the Vimy Memorial, which is a huge, immaculately clean white stone monument, with intricately carved statues. We were lucky to get beautiful sunny weather for photos, although it continued to be very cold.

Lunch was another nice baguette bag on the bus. (I wish American sandwich options were more like the French, although the French could stand to put more meat on a sandwich.) We drove to Monchy-le-Preux, where on April 14, the British had some success with a combined arms advance. We stopped at a large bronze statue of a mighty caribou, a monument to the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, who withstood German attacks on the town with only ten men. Then we proceeded down a slight hill to an area called East Trench, where Newfoundlanders and parts of the Essex regiment withstood a vicious German counterattack. Chris read a letter from a Lieutenant Keegan that described how twelve Newfoundlanders held off over 100 Germans and had a very good afternoon of “fun” doing it.

We headed to the vicinity of Cambrai and stopped in the Ribecourt British Cemetery to describe the November 20, 1917, attack by 476 British tanks, which Chris opined was the day that changed the history of warfare forever. Tanks had been deployed in the battle of the Somme, but never as a concentrated breakthrough force, and in fact the British Royal Tank Regiment counts November 20 as its founding day. It was initially intended to be a relatively focused raid, but as they prepared for the attack, the generals kept adding more and more forces, so it soon was an actual offensive, the battle of Cambrai. This battle was the first in which US troops were involved because our military railroad engineers helped build the train line and logistical facilities to transport and unload all of those tanks. From the cemetery we could see the woods (the bois d’Havrincourt) in which the tanks were hidden and the course in which they attacked through two lines of trenches in the direction of the village of Flesquières, breaking through the Hindenburg Line.

We made a brief stop at the Monument to the Nations of the battle of Cambrai, which was an interesting design that had gravel paths laid out in the shape of the Union Jack and in the center were permanent track marks from a Mark V tank interspersed with infantry footprints, commemorating the combined arms attack. Our final stop of the day was at the Cambrai Tank Museum, which is a modest affair dedicated to the battle and to the discovery and preservation of a Mark V tank called Deborah. Deborah, one of the D battalion tanks, was destroyed in the village and buried out in a farm field. In 1998, a local man named Philippe Gorczynski tracked it down and dug up the tank; as we were about to leave, he arrived and gave us a talk on the bus about how he found the tank and what it took to dig it up, save it in a barn for 17 years, and then have the museum ready for the Centenary in 2017. As I am a big tank aficionado, these afternoon activities were possibly the highlight of the trip for me.

It was about a 45 minute drive back to Arras and we watched some more episodes of the Canadian 14 diary documentary along the way. Dinner was again in the hotel.

Saturday, November 4 — The Somme

The rain has returned and some parts of the day were sunny and others were pretty wet and windy, changeable at short notice. We drove to the small town of Ayette and walked a few hundred yards into the woods to find an isolated small cemetery, one devoted to Indian and Chinese laborers. In the war about 40,000 Indian and 100,000 Chinese laborers were recruited (vs. over 1.5 million Indian army soldiers who served). Chris talked about how the Indian nationalism movement was advanced by this service and how many in the current French Chinese community came from this effort. While we drove around this morning, we watched the famous Geoffrey Malins silent movie about the first day of the Somme, viewed at the time by over half of the British population.

We made short stop outside the town of Grévillers to visit a small cemetery that contained the remains of mostly Australian and New Zealand soldiers. One of the ladies on our tour wanted to get a photo of particular grave on behalf of a colleague writing a book. Then to the town of Beaumont-Hamel, outside of which the Hawthorne Redoubt was mine-exploded on the morning of the first day of battle, famously filmed by Malins. And right around the corner, his films of soldiers in the 1st Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers were in the Sunken Lane, where Chris gave us an overview of the battle of the Somme.

Chris said there was no strategic reason to favor a battle in this area except that it was on the boundary between the British and French forces. Although the English had 1500 guns and expected to annihilate the enemy in their front, the Germans had had years to prepare their defensive positions and were hunkered down in bunkers, so they were relatively unaffected. (The British also suffered from a high percentage of dud artillery shells supplied by the US.) The orders from the generals were for the infantrymen to walk across no man’s land, expecting that they would receive no resistance. Of course, this was totally wrong. And this was the first major battle in which the majority of the British troops were inexperienced volunteers. The British part of the battle occurred over nine villages on a 15 mile front. Fifteen large mines were dug underneath the German positions, two of which we would visit today. But the results of the first day of battle, July 1, 1916, were that the British deployed 100,000 troops and suffered 60,000 casualties, 20,000 of which were killed in action, the worst day in the history of the British Army. The full battle proceeded until mid November and gained only about 10 km of territory, at the cost of over 1 million casualties on both sides.

We drove to Auchonvillers (which the Tommies pronounced as Ocean Villas) to visit the Newfoundland Memorial. As with Vimy, we had a young Canadian volunteer guide, Elliot. He described how the 29th Division assaulted the Germans. The Royal Newfoundland Regiment did not come close to meeting its initial objective and its men were pinned down until nightfall. Of the 22 officers and 758 enlisted men, all the officers were killed and only 110 members of the regiment survived. (Chris likened this to the losses of the 1st Minnesota at Gettysburg.) Elliot took us on a tour of the well preserved trenches and also the second instance of a mighty Caribou memorial statue.

We had lunch on our own at the Ocean Villas restaurant, which is a little bastion of traditional English casual food in the French countryside. I had an interesting sandwich called a sausage and chips butty. In the back of the restaurant they have a section of trenches preserved. And a lot of chickens.

Next was the town of Thiepval, which is the highest point on the Somme battle line. This was the section attacked by the 32nd Division. We visited the Thiepval Memorial, which is a giant edifice that was erected by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, commemorating the names of 72,000 unknown dead. It was designed by Edwin Lutyens, who also created the London Cenotaph war memorial. Next-door was the Thiepval Museum, which was quite good, including a number of map-oriented presentations and a giant mural done in a cartoon style that depicted the battle of the Somme in astonishing detail. They also have a replica Nieuport 17 airplane and an exhibit about aviation during the battle.

Nearby is the memorial to the 36th (Ulster) Division, a tall building modeled after a castle in Northern Ireland where some of the troops were trained. It was the first memorial on the western front. After being met by a lady bagpiper, we took a 90-minute tour with a personable Irishman named Rocky, thick of Irish brogue. He described where the German and Irish lines were and gave capsule descriptions of the actions involving four Victoria cross recipients. The divisions on the Irish left and right were both unsuccessful in their assaults, but the Irishman advanced about 2 miles before they got too far ahead of themselves and had to withdraw to avoid being a vulnerable salient. He took us into the woods to see an impressive collection of four different trench styles and described a number of the artifacts that have been retrieved from the site.

It was getting late in the day, so our final two stops were very brief. Just south of La Boisselle was the largest crater of all the mine explosions, Lochnager, an awe inspiring 21 m deep and 100 m wide. It was created by two adjacent charges that amount to 60,000 pounds of ammonal. As it is difficult to photograph such terrain, I have included an aerial photo that I found on Wikipedia.

Finally, near the town of Mametz, where the 53rd (Welsh) Division fought, we stopped at the Devonshire Cemetery, also known as the Devonshire Trench. Chris told us the sad story of two lieutenants who perceived their coming attack was doomed because of a nearby German machine gun pillbox, but they did their duty. As the 163 men of the Devonshire regiment rose from their trench, they were cut down by the machine gun before they could leave their ladders. In cleaning up the carnage, the army simply buried them in place in the trench. Chris read a wistful poem that one of the lieutenants wrote before the doomed assault.

I had hoped we would visit the first instance of a tank being deployed in combat (however ineffectively) during the Somme, through the towns of Flers and Courcelette, but it seems that some of the roads were closed for construction and we could not fit a detour into our schedule.

We drove to the city of Amiens and checked into the Mercure hotel for one night. Dinner was once again at the hotel. There is a beautiful cathedral in town, but we did not have time to visit on our own.

Sunday, November 5 — Somme, Chemin des Dames

Once again, chancy weather: sunshine mixed with biting cold and scattered showers. We started by jumping ahead to 1918, when the German Operation Michael made significant advances after being reinforced by troops from the eastern theater. We drove to Villers-Brettoneux and found a tiny sign commemorating the first tank on tank action in history, in which three British Mark IVs fought successfully against three German A7Vs. We discussed here how mostly Australian troops stopped the German drive short of Amiens.

We drove to the nearby city of Corbie, where Tour Director Chris showed us the place in which the Red Baron crashed and died on April 21, 1918. I was impressed with his level of expertise on aviation issues, compounded by many detailed questions that he answered on the bus. Richthofen was actually downed by a single antiaircraft bullet from an Australian gunner. We then drove to Sailly-Laurette on the Somme Canal and the other Chris talked about Wilfred Owens, the famous poet.

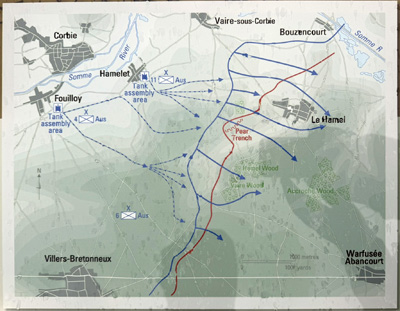

We visited the Australian Corps Memorial Park in Le Hamel and it was gratifying to finally see an Allied assault that worked as expected. Australian general John Monash made effective use of combined arms tactics with infantry, armor, and aviation to achieve a breakthrough of the German line on July 4, 1918. His force included 64 British Mark IV tanks. Some American units participated, although there was a controversy in which General Pershing ordered them not to, because they would be operating under non-American command. Nevertheless, about 700 Americans in four companies from the 33rd Division did go forward in the assault and although Pershing was furious, they were eventually forgiven.

Next was the Somme American Cemetery near Bony. This is apparently a lonely place because very few people venture into this area to visit American cemeteries. We had a tour hosted by the American director, Stephen Munro, that was quite good. Many of the troops buried here were fighting in the battle of San Quentin Canal, particularly the 27th Division, which fought under the command of the British Fourth Army in September/October 1918. They were able to pierce the Hindenburg Line, but the 27th suffered the greatest percentage of casualties of any unit in the war. In the chapel they have a list of names of unknowns and I was interested to see that the very first American casualty in the war was Col. Raynal Bolling, an aviator who was listed as a Signal Corps officer (like me).

We made a brief stop in Berry-au-Bac to visit the Monument des Chars d’Assaut roadside park that had a replica French Schneider CA-1 tank—the first French char—and a real AMX 30, a main battle tank from the 1960s. On the bus Chris talked about the 1917 Nivelle offensive; we had already seen what happened at Arras by the British, but now to the southern portion by the French Army, focused on the Second Battle of the Aisne.

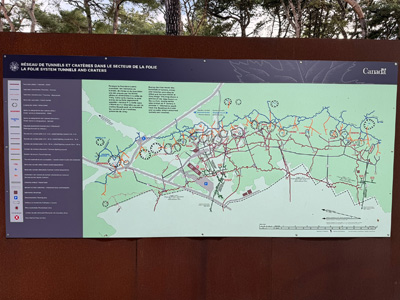

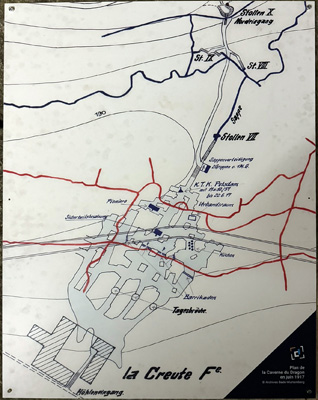

We headed to the Chemin des Dames, an ancient road that followed the crest of a mountain ridge north of the Aisne River. Here we visited the Caverne du Dragon, a series of underground limestone quarry caverns that were occupied by the Germans until 1917, when the French Army assaulted and eventually recaptured them, although at a horrendous cost. We took a 90 minute tour with a rather loquacious young Frenchman, who described how miserable life was for the Germans (later the French) who occupied these caverns: cold, humid, disease and injury prone, liable to be buried alive in any minute from opposing artillery.

We checked into the Hôtel du Golf de l'Ailette in Chamouille, which is very nice with a pretty lakeside location, but only for one night. This is right next to Champagne country and the hotel wine list had a full page of bubblies. The dinner we had in the hotel restaurant was outstanding.

Monday, November 6 — Reims, Compiègne

Another rainy start, but it soon cleared. Our first stop was Compiègne, NNW of Paris, about a 90 minute drive. The original itinerary planned to get us there on November 11 to commemorate the German surrender, but we heard that it will be closed then for private events, so we’re going out of sequence. There are a few monuments, including a very anti-German one about the liberation of Alsace–Lorraine, and the woodsy lane where famous films of Hitler were taken, but the main draw is a small museum that has the railcar where Germany surrendered in 1918 and France in 1940. (It’s actually not the same car, which was destroyed in 1945, but one of the same vintage.) On the bus ride to Compiègne, Chris gave us a thorough recounting of the events leading up to November 11 and a little about the aftermath, and then on the bus ride out, he talked in detail about the 1940 ceremony.

We drove to the small city of Fère-en-Tardenois where we had a look at the mansion Pershing used for a short while as his headquarters (previously the BEF HQ in 1914). Next was the 42nd (Rainbow) Division monument at La Croix Rouge Farm, where on July 26, 1918, regiments from Alabama and Iowa assaulted the German positions. The Alabamians were said to have use the Rebel Yell, possibly the last time it was ever used in combat.

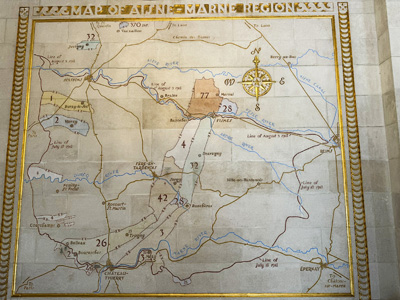

The Oise–Aisne American Cemetery is the second largest World War I American cemetery: 6013 graves, 602 of unknowns. We made a point of visiting the grave of Joyce Kilmer, the poet who wrote the famous Trees [I think that I shall never see…]. He was apparently an aide to Wild Bill Donovan In the 69th Infantry Regiment, the eventual head of the World War II OSS, and was killed by a sniper bullet on July 30, 1918. The cemetery has a very nicely done map of the campaigns in the Aisne–Marne region.

We drove to the town of Chamery, where we saw a monument to Quentin Roosevelt, the youngest son of Theodore Roosevelt, who was an aviator in the famous 95th Aero Squadron, known to be particularly brave but reckless. Then a short drive to a field nearby where his plane crashed on July 14, 1918. He had been hit by two machine gun bullets while engaged with a larger group of German fighters. Since the Germans seemed to love Col. Theodore Roosevelt, they were saddened at his son’s death and gave him a hero’s military funeral. He was eventually buried in Oise–Aisne, but in the 1950s he was reinterred to the Omaha Beach cemetery next to his brother.

In a break from the practice of the last couple of days, we made our way to our hotel as early as 4:30, the Holiday Inn in Reims. Once again a very nice, modern hotel. I took a walk around the city in a light rain and visited the gigantic cathedral. My photographs suffered from the dark weather outside, but it was still a very impressive experience. Dinner was in the hotel restaurant.