Hal Jespersen's World War I Tour, November 2023, Part 3

This is my (Hal’s) report on my trip to Belgium and France for a tour of the World War I Western Front, hosted by Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours. It is my third tour with Ambrose, the first being the 75th anniversary of D-Day in 2019, followed by Patton’s advance across France and Belgium to Germany, then the Italian Campaign from Sicily to Rome. Those travelogues are here and here. Because this report is so large, I have broken it into three parts:

- Part 1: London, Brussels, Waterloo, Ypres, Arras

- Part 2: Vimy Ridge, Cambrai, The Somme, Chemin des Dames, Reims, Compiègne

- Part 3: Château Thierry, Belleau Woods, Verdun, Meuse–Argonne, Meaux, Paris (this page)

Tuesday, November 7 — Château Thierry, Belleau Woods

A beautiful sunny day! We drove about an hour east of Reims to the French Russian cemetery at Ste-Hilaire-Le-Grand, near Mourmelon-Le-Grand. Unbeknownst to me, or anyone else on the tour, the Russians recruited two brigades to fight for the French in the Reims sector, including the ill-fated Nivelle Offensive, and here some of them rest next to a small Orthodox chapel. Next was the Ossuaire de la Ferme de Navarin, where the unidentified remains of 10,000 soldiers of the Armies of Champagne are interred, primarily the 4th French Army and some four US divisions. Gen. Gouraud of the 4th is here buried with his men. The statue on top has three soldiers, the one on the right modeled on Quentin Roosevelt pretending to be an infantryman.

Next was a field near the village of Ardeuil-et-Montfauxelles where we trooped out to find a monument to the 371st Infantry, located on Hill 188 where Cpl Freddie Stowers assaulted a machine gun nest and eventually received a Medal of Honor. The Black regiment was part of the 93rd Division, one of two Black divisions that were under French army command. We could not get very close to the small marble marker. Then not very far away was a more accessible monument, to the 369th, the “Harlem Hell Fighters.” Chris told the story of Privates Henry Johnson and Needham Roberts, who fought off a 24-man German patrol. Johnson was the first American to receive the Croix de Guerre and he was eventually awarded the Medal of Honor by Pres. Obama.

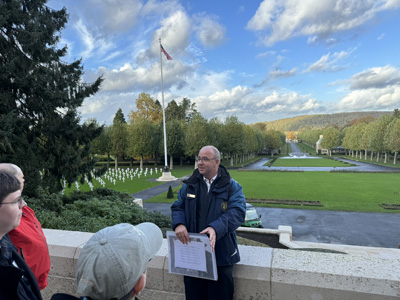

Then 90 minutes to Château Thierry. Chris gave us a brief overview of the campaign along the way and then we were let loose to find lunch in town. I ended up with a rather mediocre buckwheat crêpe. Nearby is Hill 204, the Château Thierry Monument, which is a stupendous white stone temple with a beautiful view of the Marne River. There is a very informative museum of the campaign underneath. Then to the Aisne–Marne American Cemetery where we got an extensive tour with the director, Ian Stephenson. There are 2,289 graves and 1,060 names of the missing in the lovely small chapel. We ended up witnessing the lowering of the US flags and the playing of Taps.

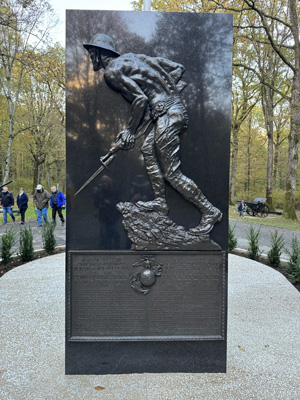

Back on the bus, we headed to nearby Belleau Woods—which abuts the cemetery and defines its curved layout—officially named Bois de la Brigade de Marine. This is a mystical place in the history of the USMC, where they stopped the German Blücher Offensive at its farthest point, on the road to Paris. There is a small memorial grove with a number of artillery pieces and there are walking trails that go by still visible foxholes and trench lines. In the waning light, I didn’t attempt to photograph any of these.

It was 45 minutes back to Reims. Dinner at the hotel again.

Wednesday, November 8 — Verdun

Clear skies to start, turning low overcast, but pretty cold today. (Last night Chris told some of us that this particular World War I tour has had the worst weather.) It’s about a 90 minute drive to Verdun and along the way Chris gave us an overview of the 1916 battle. Verdun is the heaviest shelled city in history and France lost more men there than America has in all of its wars. The French built 22 major fortifications around the city, although they have decayed somewhat since the 1870 war and the French were ill-prepared for the German attacks.

The drive was a bit nostalgic for me because it was on the autoroute that I drove a number of times in 1970s trips from our station in Germany to Paris. (At that young age, I knew squat about WWI.) We exited the autoroute and drove north on the Voie Sacrée, the supply road to the city that received the Croix de Guerre. Our first stop was the Ossuaire de Douaumont, home of the remains of 130,000 men, both French and German. There are also 15,000 graves in a cemetery out front. It’s a huge, rather depressing structure. At its base is a series of windows through which you can clearly see large piles of bones, which I decided to avoid photographing out of a modicum of respect. We watched a movie about the terrible conditions in the battle and then went upstairs to a giant room, reminiscent of a train station, in which carved inscriptions identified a variety of units and groups whose bones are about. No photos were allowed, but I included one from Wikipedia that is tinted an odd shade of red for some reason.

We passed through one of the dead villages, where only signs remain to document building sites, but everything is gone and the area can’t be reoccupied. Some estimates are that 60 million shells landed in the area, and there certainly some still live, including poison gas rounds. Capt. Charles de Gaulle was wounded here and evacuated, which providentially meant that he didn’t get killed prematurely. At the Trench of Bayonets, a monument remembers the 137th Infantry Regiment, which was standing in their trench with bayonets fixed when a shell buried them alive, leaving their bayonet tips sticking up through the dirt. The trench is protected now by a massive brutalist concrete structure, but the bayonets have been stolen by vandals.

Fort de Douaumont is a large concrete and stone structure mostly buried, but was further fortified during the battle by hastily poured additional layers of concrete. In the third day of the German attack in February 1916, a small raiding party entered the fort and found it virtually unmanned while its 57 reserve garrison troops were away at a conference, so it fell into German hands. They had to carve new gun ports into the rear of the fort, which now faced the French. A number of the guns had been removed by the French in 1915 because they were needed elsewhere on the front, but we stood inside a turret for a retractable 155 mm gun. Andre Maginot was stationed here and undoubtedly took inspiration for his Maginot Line forts. There are a lot of dark tunnels to explore today, which are wet and have creepy stalactites. There is a memorial to German troops who perished inside when a soldier heating coffee ignited an artillery magazine. The French eventually retook the fort in an October assault by three divisions, but over the months, it cost them about 100,000 men to do so.

Next was the excellent Mémorial de Verdun history museum, which has lots of multimedia displays and innovative use of 3D maps. If it had been a little more English friendly, it would be outstanding. But it was stylish and very comprehensive. Lots of weapons, equipment, and artifacts. They estimate 400,000 wounded on both sides, 300,000 killed for the February–December battle.

Nearby is the dead village (“Mort pour la France”) of Fleury-devant-Douaumont. The museum we just visited was on the site of Fleury’s train station. In the big German offensive that started June 11, the elite Alpine Corps attacked the village of 422 folks behind a bombardment of phosgene gas. Over a month, the village changed hands 15 times, but the Germans never advanced further and the lines stabilized. There is a small chapel now and a few walking trails that correspond to the original village streets, going past former buildings that are now deep craters.

Our final stop in the waning daylight was on the left bank of the Meuse River, a battle memorial to the 69th Infantry Division entitled Le Mort Homme, or Dead Man’s Hill. It has a skeleton statue wrapped in a flag with the inscription “They Did Not Pass.”

Our hotel in Vienne-le-Château, Le Tulipier, was about a 45-minute drive, to the western edge of the Argonne Forest. It’s a small hotel in a one-horse country town. This begins a three-night stay, a real plus for weary luggage handlers. Dinner at the hotel was excellent, our first dinner in France in which a traditional cheese and small salad course was served before dessert.

Thursday, November 9 — Meuse–Argonne

We started off in a light drizzle for the first hour, but the rest of the day was clear or overcast. When the wind blew, it seemed bitterly cold, although my weather app indicated it was only about 50°. On the bus Chris gave us an overview of the Meuse–Argonne Campaign, which was fought over 47 days by 1.2 million Americans, eventually reaching a strength of two field armies. They had 190 French light tanks and 4,000 artillery pieces, including some 14-inch railroad guns. Four million shells were fired. Chris described briefly a few of the preceding much more minor US battles: Cantigny, Fismes, and reducing the St. Mihiel salient. He talked about George Marshall, who was moved from a combat post to a staff job under Pershing and was given the job of planning to move 500,000 men in 17 divisions from St. Mihiel to the starting point for the campaign in only three weeks, using an inadequate road network over rough terrain in secrecy.

We drove about a half an hour to the town of Romagne-sous-Montfaucon, where we met a man named Jean-Paul de Vries, a Dutchman who moved to this area in his youth because of his fascination with relic hunting and the first world war. He operates a small private museum that displays many of the 300,000 artifacts and relics he has found within a 5 km radius. Although I cannot say that I am particularly interested in individual relics, the sheer scale of his efforts opened my eyes. It is quite a thing to see a wall covered with multiple hundreds of shovels or canteens or shells or bayonets. With Jean-Paul as our tour guide for the day, he first took us to the town of Nantillois, where one of our tour party had a grandfather who served in an artillery unit stationed there. He identified the particular stretch of woods in which that unit was positioned, as the 79th and 80th Infantry Divisions pressed on to Montfaucon.

Next we went to the Madeleine farm, site of multiple attacks by the 80th, 3rd, and 5th Infantry Divisions. We saw the site of the exploits of PFC John Barkley, who on a lone patrol between the lines found a broken German machine gun, fixed it, and then took up a position in a disabled FT 17 tank. He drove back two German assaults, including direct fire from a 77 mm cannon, and received the Medal of Honor for his heroism. For a second example of heroism, we went to the nearby village of Cunel (population 16), where a Lt. Samuel Woodfill personally assaulted three German machine gun nests, killing all of enemy soldiers, and also receiving the Medal of Honor. We visited a small church named after Saint Christopher, noting the many bullet holes in its façade, including where three local civilians were executed up against the wall by World War II Germans using machine guns.

After having a nice sandwich lunch at Jean-Paul’s museum, we went to the Romagne German cemetery, and then the adjoining civilian cemetery, which has the distinction of hosting one of the 12 firing squad members who executed Mata Hari. Somehow this soldier received the Legion of Honor for doing this, which mystifies me. (It also mystified me to hear the story of how French soldiers back then received only a certificate for their service and then had to go to a local jewelry store to buy the physical medal.)

We drove to a hill called Côte Dame Marie, where we took about an hour walk through the woods, about a mile on a path that followed the local portion of the Hindenburg Line. We saw a well preserved bunker, one that was not created for firing, but for sheltering artillery soldiers. We also saw numerous shell craters caused by large caliber American artillery, and some trench lines. Finally, we stopped at a monument remembering the assault on Côte de Châtillon by the 42nd (Rainbow) Division on October 14. The 84th Infantry Brigade was led by Douglas MacArthur in the assault against the strongest position in the German Kriemhilde Line (one of the subsidiary lines that composed the Hindenburg). Capt. Harry Truman’s artillery battery was part of this assault, but he was not mentioned in any of the text on the memorial, a sign provided by the MacArthur Memorial Association. Perhaps there was some lingering resentment between MacArthur and Truman?

Dinner again was at the hotel.

Friday, November 10 — Meuse–Argonne

The weather has turned out to be pretty constant after the bomb cyclone passed: scattered drizzle, windy, and cold again today. Our first stop was in Varenne-en-Argonne to visit the Pennsylvania state monument, commemorating the actions of the 21st Infantry Division. (Ever since the battle of Gettysburg, the state of Pennsylvania has been grandiose monument obsessed.) There is a panoramic view from which we could see a hill in the north where Harry Truman‘s artillery battery was stationed. We also heard the non-WWI story about Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette being captured nearby in this town as they were attempting to escape to Belgium. Then we drove back to Romagne to pick up Jean-Paul again.

Our next stop was Montfaucon, which is a high hill and a key objective for the first day of the campaign. Some of the Americans referred to it as Little Gibraltar. There is a tall American monument on the top, but we found that it was closed today for some reason, so we could not go inside and see the campaign map, to which I had been looking forward. Chris told us the story of the attacks, in which the 39th Infantry Division and the 4th Infantry Division were to attack on the left and right, and the 79th Infantry Division was supposed to go up the center. However, the assault did not go well and the 79th squandered their strength by sending regiment after regiment in individual assaults. All of the battalion officers were casualties. Before the war there was a town on the top of the hill, but it has been since moved down the slope. Only the ruins of a church remain, along with as many as 28 bunkers. We visited one bunker on a stroll around the summit. The previous towns had been destroyed at least nine times over history going back to the Romans, but the most interesting one was a battle between 1,000 French farmers and 19,000 Vikings, in which all the latter were killed.

Next we visited the town of Cheppy, where there is a Missouri state monument, but the draw here is this was the location of George Patton leading a tank brigade in combat. We saw where his French light tanks struggled up the hill and where he was wounded. (He was actually walking in between tanks out in the open.) Then to Vauquois Hill, where we ascended a steep gravel staircase to see not only a commanding view of the surrounding farmland, but also immense craters. This hill was actively contested from the beginning of the war and the opposing trench lines started out as close as 10 meters apart, opposite sides of the street in the small town. Both armies got to digging and exploding giant mines under their opponents, causing the trenches to get bigger and bigger. The hill was eventually taken by the 35th Infantry Division.

After another baguette lunch at Jean-Paul’s museum, we headed to a road junction near the town of Binarville, where there is a monument to the 9th Cuirassiers, part of the French Fourth Army. Our interest, however, was in the US 368th Regiment, which was a Black unit liaising with the French on the far left flank of the US First Army. The Black regiment never received the recognition it deserved for its actions in the battle, but when the French monument was raised, they told the veterans of the 368th to consider it a monument to them as well.

Next we addressed the famous Lost Battalion. All morning on the bus we had been watching the movie of that name, starring former child actor Ricky Schroder, and it was actually pretty decent. Part of the 77th Infantry division, the 1st battalion of the 307th regiment was attacking through the Argonne Forest when its neighboring units could not advance and had to withdraw, leaving the battalion isolated and cut off from communications. Of the 554 men, only 194 survived to be rescued five days later. They suffered numerous attacks by German units and also a two hour blue-on-blue friendly fire artillery attack from their own division. There was a famous incident near to my Signal Corps heart in which a carrier pigeon named Cher Ami was sent with an emergency message to stop the American shelling, and although he was shot up and lost a leg and an eye and had chest damage, he still managed to fly back to division headquarters. The pigeon received the Croix de Guerre for this gallant feat and is now on display at the Smithsonian History Museum. After visiting the Lost Battalion monument (which features the pigeon), we drove to their actual site, which is on a very steep slope in the woods. It was steep and wet enough that I did not attempt to slide down the hill to see the foxholes, which still exist.

Our final destination was the town of Chatel Chéhéry, where we visited a plaque commemorating the exploits of Sergeant York. Unbeknownst to me, there is bitter controversy about the real version of the story. Part is the actual location of his exploits, with two competing theories, although not really very far from each other. Jean-Paul was part of the investigation that found artifacts supporting one of the locations. More significantly, the generally accepted story that York single-handedly destroyed 35 machine gun nests, killing 25 Germans, and capturing 132 prisoners, for which he received the Medal of Honor and lasting fame, might not be entirely true. York was in a patrol of 12 Americans and some authors claim that these exploits were the result of the entire patrol, not one individual corporal (as York was at the time). We also took a walk around the back of the town to the Sergeant York Trail, where we got to see the two competing areas in which the exploits occurred.

Once again, dinner was at the hotel. This has been an unusual tour in that all of the hosted meals have been in hotels, but fortunately most of them were very good to excellent.

Saturday, November 11 (Armistice Day) — to Paris

We headed back to Romagne for the Meuse–Argonne American Cemetery, an appropriate destination for Armistice Day. It’s the largest American cemetery in Europe, with 14,246 graves, including over 450 unknowns and almost 1,000 names listed as missing. We had a brief informal ceremony in the chapel to lay a wreath on behalf of our group. I was surprised to be selected to lay the wreath, because I was the tallest veteran in the group. We visited a few graves, most notably three unknowns in a row who were the three not selected to be the US Unknown Soldier in Arlington. Chris told a moving account for how the selection process and transport of the casket to the US happened. We finished our visit just after 11 AM, the exact time 105 years ago that the guns fell silent. We were fortunate to have a bright sunny day. The marble headstones were gleaming white and each was decorated with American and French flags.

But we went back 105 years and one minute by driving to Chaumont-devant-Damvillers to visit the death site of Henry Gunther, the last man to die before the armistice. We marched through a muddy farm field to the trench line of the 313rd regiment of the 79th Infantry Division and Chris planted a small US flag in the approximate position that Gunther left to charge a German machine gun in the woods.

Now a long stretch on the bus, during which we watched the Peter Jackson colorized film They Shall Not Grow Old. There was a brief lunch break on the autoroute, near the town of Valmy, site of a famous windmill and a battle in 1792. Continuing on the road, Chris summarized early fighting in 1914, including the BEF fighting retreat to the critical First Battle of the Marne and then the German pullback to focus on the Race to the Sea. Then he talked about the Spanish Flu epidemic and how it affected the war effort, particularly the German. We also watched the antiwar musical, Oh What a Lovely War—man, that is one weird movie. We finally reached Meaux, just east of Paris, to visit the Musée de la Grande Guerre du Pays du Meaux, which is located on part of the battlefield of the First Battle of the Marne, 1914.

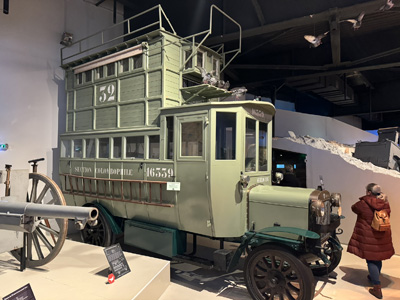

The museum is very modern and graphically stylish. It is based on a donated private collection of uniforms, weapons, and artifacts, all in pristine condition, and many in interesting dioramas. Although they have a number of military leader personalities catalogued, they are quite deficient in maps, both static and animated (the latter being a hallmark of most modern war museums). Many of the displays are trilingual, but some of the films are not. I can’t say I acquired any new insights into the war.

Outside is a giant monument, 26 meters high, donated to France by the Americans, called Tearful Liberty or the Marne Battle Monument. It was dedicated in 1932 in honor of the Allied troops who died in the battle. This afternoon was the first in two weeks that I didn’t have to wear gloves and five layers of clothing.

Our airport hotel, the Pullman Paris Roissy CDG, was about 45 minutes away. It is very modern and comfortable—luxurious, really, worth bookmarking. (And in fact I will be returning to Paris next month and have changed my hotel booking to this one.) Our farewell dinner was in the hotel.

This was one of the best military history tours I have ever taken. Kudos to Chris, Chris, and Klaas for almost perfect logistics and great educational content. And there were lots of nice folks with whom to spend a busy two weeks.

Sunday, November 12 — Home

Since I chose to fly on British Airways, my flight back was from CDG to LHR to SFO, leaving in the morning and arriving late evening the same day. There is an airport terminal train right across from the hotel, and it appears that you can also get the RER to Paris right there. Once in the right terminal, the crowds were really large and there were significant waits at security and passport control. Our flight to London was delayed quite a while because so many passengers were late getting through the lines.

London Heathrow was a madhouse as well. I was surprised that I had to process through security again, even though I never left Terminal 5. My BA flight back on a 777 was superior to the 380—door on the aisle, adequate storage cubbies, reliable power, and just-about adequate lie-flat room.